In a world where cultural diversity and plurality is not only cherished but respected profoundly, repudiating the national languages bill would only do an utter disservice to the federation

The National Assembly’s Standing Committee on Law and Justice repudiated a bill seeking status of national language for major Pakistani languages. The bill was tabled by the PML-N legislator Marvi Memon. Only a few months ago, the Standing Committee of National Assembly on Information, Broadcasting and National Heritage adopted a resolution to declare 13 mother languages of Pakistan as national languages and establish a Languages Commission for scientific research and policy formulation to promote Pakistani languages.

An intransigent bureaucracy in cahoots with myopic political leadership crumpled the bill that could have assuaged pervasive agony among federating units that has plagued the federation for more than six decades. Spurning the bill, Special Secretary of the Law Ministry Raza Khan spouted that there should be one national language of a nation. Twisting historical facts he also said that the country had already suffered the East Pakistan tragedy in 1971 as a result of the decision to declare both Urdu and Bengali as national languages.

Bereft of political sagacity, the reference to East Pakistan debacle was too egregious and distorted. Clinging to a state of denial even after four decades of a tormenting tragedy is an alarming portent for years to come. It is an undisputed fact that a disdainful denial to Bengali language actually fractured the federation in its formative years that eventually lead to fragmentation. A reluctant and belated recognition of Bengali language was too late and too little to ameliorate the situation.

In a world where cultural diversity and plurality is not only cherished but respected profoundly, such ignoble mindset will only exacerbate the intractable challenges faced by the country. Cultural heterogeneity is an indelible reality that ought to be recognised and converted into a unifying factor rather than a divisive one.

It is ironic that an anachronistic narrative dominates the country, which is already on a perilous course. One language, one religion and one nation dogma has already last its glow. There are copious examples where more than one language has been accorded the status of national language.

Few such examples are cited here. Arabic and Berber are national languages in Algeria. Finland has two national languages; Finnish language and the Swedish language. Neighbouring India has 23 official languages (Assamese, Bengali, Bodo, Dogri, English, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Kashmiri, Konkani, Maithi, Malayalam, Manipuri, Marathi, Nepali, Oriya, Punjabi, Sanskrit, Santali, Sindhi, Tamil, Telugu, Tulu and Urdu). Nigeria recognises three ‘majority’ or national, languages; Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba. Singapore has four official languages viz. English, Chinese, Malay and Tamil. South Africa has 11 official languages namely: Afrikaans, English, Ndebele, Northern, Sotho, Swazi, Tswana, Tsonga, Venda, Xhosa and Zulu. Switzerland has four national languages including German, French, Italian and Romansh. In Hong Kong English and Chinese are official languages. In Sri Lanka Sinhala and Tamil are official languages.

Pakistan is a federation created by a mosaic of discrete nations with distinct cultures and history. Cementing federating units into a nation on the basis of religion or a manufactured identity is a proven failure. Federations can only survive and thrive on the principles of political, cultural and economic justice.

In Pakistan, seeds of discontent were sown right from its inception when Bengalis demanded Bangla to be the national language along with Urdu. West Pakistani establishment loathed Bengalis and were rabidly against the demand of Bengali language. They wanted to rein in the nascent country through a cultural hegemony and therefore exalted Urdu as a symbol of Islam and two-nation theory. It was insinuated that if any other language was made official language it will jeopardise national unity and security.

Liaquat Ali Khan and his coterie was the protagonist of this phony philosophy. Even a sturdy-minded Jinnah was influenced by this notion. During his visit to Dacca in March 1948, he belaboured significance of Urdu as the only national language. In spite of being deeply revered by Bengalis, his views met tough resistance throughout his visit.

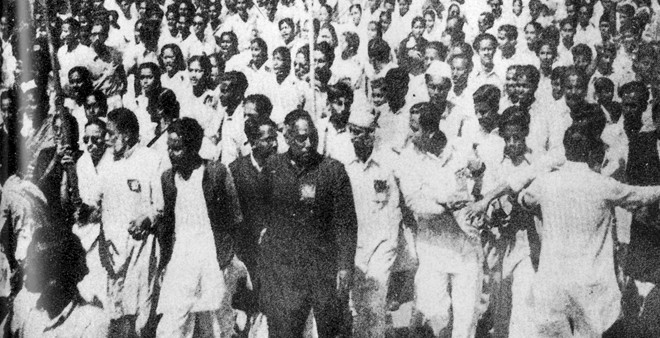

Addressing a humongous public gathering at the Race Course ground he admonished that "let me make it quite clear to you that Urdu and no other language will be the state language of Pakistan". Obstinacy prevailed during the following years and the volcano erupted on 21st February 1952 when police brutality was used to pummel a rally of students in Dacca resulting in death of young students.

In a tardy attempt to resolve the language conundrum, the then Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra presented the Language Formula on May 7, 1954. The formula proposed both Urdu and Bengali to be official languages and authorised head of the state to accord same status to other provincial languages on the recommendation of the concerned provincial legislature. It also recognised equal status for all provincial languages for examination for the central services.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan asked a question if the provinces could use their languages as official and court languages, Bogra replied in affirmative. Abdul Sattar Pirzado from Sindh, Khan Abdul Qayoom Khan from NWFP and Sardar Shaukat Hayat Khan from Punjab hailed the formula. Mir Jaffar Khan Jamali a member of Sindh Legislative Assembly welcomed the initiative. Young Sindhi Muslim Jamaat congratulated the prime minister and urged the Sindh Assembly and the head of state to declare Sindhi one of the state languages.

However, an Urdu-obsessed lobby castigated the proposition. Maulvi Abdul Haq whimsically argued that Bengali has been nurtured by the writers of Bengal and Urdu has developed in the tradition of Islamic culture and learning. Adding extra flavour, he asserted that the two-nation theory owes its origin to Urdu and is based on the existence of Urdu as the language of all Musalmans.

Another cleric Maulana Ehteshamul Haq Thanvi denounced the formula by saying that nobody could have imagined that one of the basic principles of the independence fight could be flouted like this. The Central Refugee Rehabilitation Board of Karachi demanded that Urdu should be the national language of Pakistan. Maulana Abdul Hamid Badayuni of Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan lamented that he could not accept the idea of Pakistan having two official languages. Raja Hasan Akhtar of Punjab Jinnah Awami League, Khawaja Abdul Rahim and Agha Shorish Kashmiri said that Urdu was a language that far more than any other provincial language embodies the best that is in Islamic culture and Musalman tradition.

Z.A Suleri, editor of The Times of Karachi and President of the Council of Pakistan Editors called for a strike. Some prominent Karachi-based newspapers that joined the strike call included Jang, Millat, Time of Karachi, Morning News and The Dawn. The Dawn did not publish its edition on May 21.

By the time Bengali was constitutionally recognised as one of the national languages, much of the water had already flown below the bridge. Bengal nationalism transcended the language issue and snowballed into a more radical nationalist movement emphasising on more inflammatory issues of political and economic exploitation.

A reaction of similar proportion, yet with a lesser violence, dominated public sentiment in Sindh. The Sindhi language had an enviable history. It was made official language in 1848 by the governor of Sindh, Sir George Clerk. It was made language of official communication and qualifying Sindhi examination was made mandatory for civil servants in 1857 by Sir Bartle Frere, the then commissioner of Sindh.

Karachi at the time of partition had a population of 0.4 million with 61 per cent Sindhi-speaking compared to only 6 per cent Urdu-speaking population. Sindh erupted into a mass movement when the Commission on National Education aka Sharif Commission of Ayub era declared Urdu as the only medium of instruction from the sixth grade. The movement turned violent during language riots of 1971 and 1972. A demand for recognition of Sindhi as one of the national languages has been the lynchpin of nationalist movement in Sindh.

Likewise, Seraiki, Pashto, Balochi, Brahvi, Hindko, Shina, Torwali and other languages own a rich treasure making Pakistan a cultural bouquet. Recognising and promoting these languages is not tantamount to disparage Urdu by any means. However a persistent denial of these languages has been fueling acrimonious sentiments and unraveling communal harmony. Repudiating the national languages bill would only do an utter disservice to the federation.