Dr Sikandar Hayat provides a refreshing and insightful analysis of the final phase of Pakistan Movement by recasting and reinterpreting the history and leadership of Jinnah

In the last four decades, particularly after the breakup of Pakistan in 1971, different interpretations have emerged on the subject of creation of Pakistan. Some have argued that the place was ‘insufficiently imagined’, others have equated its birth with ‘shameful flight’ of the British while some scholars are still trying to "make sense of Pakistan".

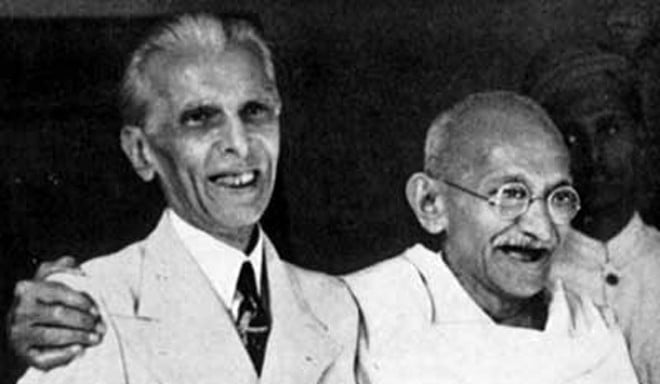

The questions on the nature, origins and circumstances of Pakistan’s birth have also aroused considerable interest on the role and leadership of Jinnah -- the founder of Pakistan. However, most of these studies have looked at Jinnah as some kind of passive bystander portrayed as a ‘saviour’ driven by personal ambition to be the ‘sole spokesman’ of Indian Muslims. It is ironic and sad that until 1993, the first volume of his papers could not be published. Patrick French has incisively remarked that neither Indians nor Pakistanis seem keen to see him as a ‘real human being’.

Dr Sikandar Hayat in his updated and revised edition of his book, The Charismatic Leader: Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and the Creation of Pakistan (Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2014) challenges these explanations and interpretations, and draws attention towards the centrality of Jinnah as ‘the charismatic leader’ who, with a commitment of purpose, integrity, dedication and unflinching support from his followers, at the most critical juncture in the history of Indian Muslims, offered the ‘formula of a separate state’ that led to the creation of Pakistan. He dispels the notion that Jinnah used the idea of a separate state as a ‘bargaining counter’ to seek concessions from the colonial rulers.

Dr Hayat brings persuasive arguments and evidence together to make us believe that during the distressful period of 1920 and 30s for the Indian Muslims, Jinnah was the man of the moment. Principled and determined, Jinnah was a man with a mission, who had a clear vision and who knew how to accomplish it. He makes a persuasive plea and argument to recast, re-imagine, re-interpret the history of Pakistan Movement (1937-47) and the studies on Jinnah’s leadership by centre-staging him as the ‘charismatic leader’.

Of course, this phase of Pakistan’s history is well-researched and studied but the leadership of Jinnah has begun to attract scholars only recently. Why Jinnah mattered then? Why is he relevant today and for times to come? How studying his leadership is vital for understanding the adversarial circumstances under which he provided not only hope but a concrete formula to the dismayed and distressed Muslims of undivided India. Dr Hayat has been researching and refining the concept and theory of charismatic leadership for over two decades and, in the process, he provides a refreshing and insightful analysis of the final phase of the Pakistan Movement.

In focusing on the charismatic leadership of Jinnah, Dr Hayat makes three important contributions in refining, synthesising and expanding the theory of charismatic leadership; first, connecting charisma with institutionalisation, second, dispelling the notion that charismatic leadership is always/mostly irrational, third, synthesising personal attributes of leadership with situational circumstances. All three contributions resonate and could be instructive for leaders and political parties in contemporary Pakistan.

I have found four chapters in his book of particular interest that are theoretically and conceptually enlightening (chapters 1, 3, 4 and 5). In the first chapter, Dr Hayat takes the readers into confidence by explaining what charismatic leadership is and why Jinnah excels as a charismatic leader? Like many other scholars, he also starts with the original source -- Max Weber, who defined, conceptualised and theorised the relevance and need of the charismatic leader.

Operationalising the concept of charismatic leadership through the lens of Weber, Dr Hayat goes beyond and weaves the arguments of Ann Ruth Willner, Carlyle and Dankwart Rustow to point out the extraordinary qualities of his leadership, and how such a leader is able to inspire ordinary citizens to follow his calling and they exalt him. Charismatic leader has ‘prophetic qualities’, integrity, compassion, commitment of purpose and is able to evoke devotion among his followers. A charismatic leader has emotional appeal among his followers, who bond, listen and follow the leader with devotion. These are extraordinary and rare qualities which establish an unbreakable bond between the leader and the follower.

Supernatural qualities and myths abound and followers’ allegiance and obedience to the charismatic leader progressively grow. According to Dr Hayat, among the Muslim leaders during that period (see his chapters 3 and 4 on Leadership Crisis) Jinnah was the only leader who had these personal qualities and could establish personal rapport with distressed Indian Muslims. Thus, Dr Hayat insists that charisma is a function of both, ‘personal’ and ‘situational’ factors and that aptly describes Jinnah’s role in the creation of Pakistan. In that spirit, Dr Hayat, amplifies the concept, adding that charismatic leader is sober, responsible and rational and does have ‘passions’ tempered by ‘reason’.

The author is conscious that the rise and fall of a charismatic leader could be ephemeral depending on the ‘crisis’ situation and need of people at the moment (think of Churchill at the end of Second World War, Nkrumah at his fall). However, he points out Jinnah was different as he did not rely only on personal attributes but made consistent efforts to develop Muslim League as a political party -- which is a hard sell. He adds theoretical rigour by pointing out how some exceptional leaders are able to ‘routinise’ charisma in a social or political institution. In case of Jinnah, Dr Hayat argues that some of his charisma was inevitably placed in the Muslim League, as the people saw it strictly as Jinnah’s party.

Such a perspective could arouse greater curiosity and perhaps more rigorous research on various facets of Jinnah’s leadership. Dr Hayat’s updated and revised version stops at the creation of Pakistan and does not reflect on Jinnah as Governor General of Pakistan. Could he still be considered charismatic? May be Dr Hayat or some younger researcher could test if charisma holds beyond the creation of Pakistan?

The study offers a new angle to the leadership of Jinnah and opens up new avenues on the subject. All those who are interested in understanding why political will, clarity of purpose, a sense of vision, mission, integrity and dedication to a cause is essential for leadership, will find the study refreshing, inviting and instructive to understand the woes and future direction of Pakistan.