Deconstructing the visual representation of a ‘golden-era’ of Pakistan that is seen as more liberal, modern and tolerant of others

In recent years there have been a number of articles which have explored the visual representation of a so-called "golden-era" of Pakistan. Nadeem F. Paracha has been at the forefront with his attempts to show a Pakistan which many would struggle to recognise today. Just recently there was an article by Ally Adnan in The Friday Times which explored the history of Eid greeting cards via the writer’s own experiences; a more compelling and detailed account of vintage Eid greeting cards and their origin has been done by Yousuf Saeed. And then there was a short pictorial essay by Amna Khawar on vintage travel posters capturing the romantic side of Pakistani tourism. Many of these images relate to the 1950s and 1960s.

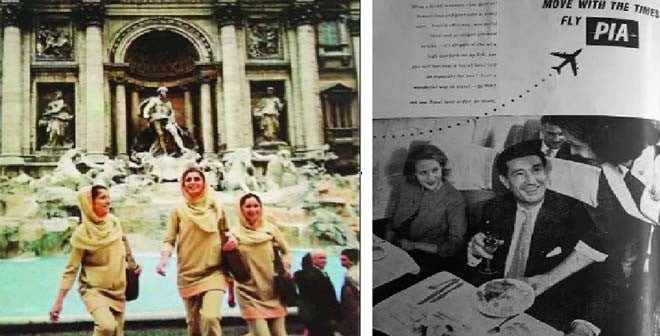

As a historian I have been thinking about these articles along with my own research, which has been exploring women’s representation in public spaces in the formative years of Pakistani history, especially the women who worked for Pakistan International Airlines (PIA). I have been fascinated with the role of nostalgia and how this has been shaping the popular imagination in recent years. The pictures collectively evoke a period that is seen as being more liberal, tolerant of ‘others’, modern, sassy, energetic, optimistic and laced with a sprinkling of the colonial hangover.

An early example of this is an ad by PIA from 1960, with the tag line "Move with the times." PIA was one of the leading brand ambassadors for Pakistan and, combined with the emergence of the jet-age, there was a growing tourism industry that is virtually non-existent now.

More broadly, and used as a source, these images also depict the changes that have taken place in Pakistan and how these are reflected in society. While much has been written about the history of Pakistan, this has largely tended to focus on the political issues, ideological debates, economic concerns or the political leadership. Rarely do we get to glimpse history through the prism of the societal and cultural changes taking place. The ordinary lived experiences of people, especially women, rarely get coverage in the official histories, which are more concerned with the high politics. Yet, if we start to scratch around the pages of old newspapers, magazines, folklore, literature, and personal narratives, there are many untold stories waiting to be explored and unearthed.

So why this fascination now? There are a number of factors converging at the moment which are in many ways compelling commentators and writers to re-visit this history. The political changes and gradual encroachment of religious conservatism in Pakistan makes us want to explore alternative national histories. This is almost a reaction to the current political climate, which has rendered many helpless in their attempt to preserve a more secular and liberal vision of Pakistan, which was seen to be more prevalent in the early days of Pakistani history.

The distortion of history, both intentionally and now as a default position because the effect has been so pervasive, has helped to re-write how we understand and analysis the early history of Pakistan. This has been a gradual process but, I would argue, something that started especially after the break-up of Pakistan in 1971. The reaction to the split was an attempt to force bind a greater unity amongst the people and consequently more religiosity was prescribed to keep the nation from further fragmentation. This rather dogmatic approach meant a more exclusive understanding of Pakistani identity which frowned upon anything that deviated from the acceptable norms of the state-view.

The 1970s were also importantly a watershed for Pakistan because a number of factors converge together. The power of the petro-dollars and Saudi Arabia, the state-sponsored Islamisation during the Zia period, the rise of the pan-Islamic identity, the Russian invasion of Afghanistan, American interests in Pakistan, coupled with the break-up of Pakistan at the start of the decade result in a nation that was seeking a new identity. The response was almost an attempt to finally break away from the shackles of imperialism and create a new post-colonial nation. The replacement, however, has seen this being replaced by a different form of colonialism, one that relies heavily on Saudi Arabia and ironically a dichotomous relationship with America.

Pakistan has thus undergone a vast amount of change during the past forty years. Within all this change, which has been confused and contradictory at times, there is sentimentality and nostalgia for a period that seems so distant. The era of the 1950s and 1960s when, women were optimistic of their role in the nation-building project, and were visible in public spaces; economic prosperity offered hope for the future; a young nation looking and embracing internationalism; and the buoyancy and optimism of independence still reverberating. The reality may have been different but memory is quite subjective and revisionist.

But sixty-eight years on, the optimism and expectations have somewhat dampened and have been replaced by cynicism, lack of faith in the state apparatus to deliver the basic needs for its people and a religious-ideological schism which is pulling people apart.

So it is within this context that increasingly there is a re-evaluation of trying to understand that period. It is in a sense a desperate attempt to hang on to a past that will be familiar to many but more radically it offers a space in which a nation is still trying to define itself. These cultural and social spaces are powerful, just as the margins are; so within these confines there is an opportunity to construct and revise a history that has become so distorted. Indeed History is never static; it is continually changing and is shaped by the present. Similarly, memory is equally revisionist and it is the fragility of the present, which compels many to seek answers in the past and contextualise this history in the present.

By exploring these alternative spaces and histories of our collective past, we can perhaps better understand and hope for a more compassionate future.