Afshar Malik’s decision to move away from his usual set of visuals is a great leap into the unknown, and is both courageous and significant

You must have heard this analogy that if a man who died 50 years ago returned to this world, he would be shocked to see the use of mobile phones and internet for communication instead of letters and landline telephones. Likewise, a Pakistani who passed on twenty years ago will find it difficult to recognise our present day urban spaces lined with barriers, barricades, barbed wires, sand bags, high boundary walls with sharp metal grills and gun-toting policemen.

The security paraphernalia is increasing and we the citizens are becoming immune to these intrusions in our public aesthetics. In the coming days, the architects might decide to design structures keeping in view these security needs. One can imagine the façade of a future house or office blocks layered with barbed wires or decorated with steel grid. Perhaps in the coming years, the humans too might be barricaded like the buildings (you can imagine that by looking at the uniform of riot police).

All these additions in our social and visual surroundings have affected our arts too. A number of artists are appropriating these objects of security in their works; for example, Bani Abidi has employed pictures of barriers and barricades in her Security Barriers A-L, the Inkjet prints from 2008. Several other artists, like Farida Batool and Amna Ilyas, have also incorporated the reference of barbed wires in their drawings and mixed-media installations.

The new works of Afshar Malik can be read or interpreted in a similar way. The artist has utilised wires to mould and make his forms; even though he is not concerned with the idea of barriers, their strong presence in the present social structure could have had an impact on the vocabulary of this important artist of our times.

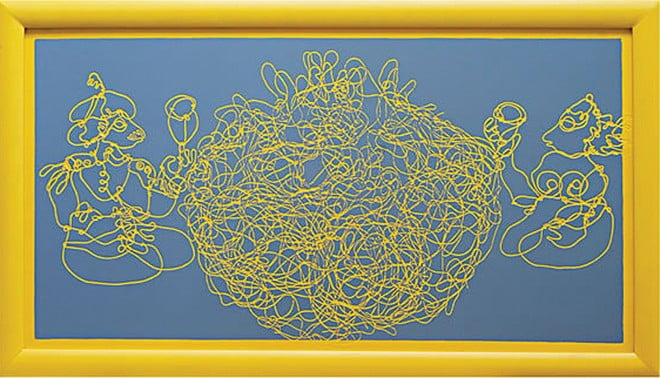

In his new works, one can witness an apparent but not sudden shift in the artist’s aesthetics. In contrast to his earlier works, loaded with textures and adorned with colours and forms, the visual strategy in the present body of work indicates a sense of sparseness. However Malik’s training and experience as a printmaker has resurfaced; since these works, all collographs, have a single colour with images drawn through turning and shaping metal wire. Some of these prints are rendered in singular white, yellow or other colours; in a few, the drawing appears in white while the surface has a uniform colour.

Most of the imagery is constructed (in the literal sense because it was all joined with wires first before getting its impression on the thick mount board) focusing on human figures in multiple compositions. In several works, the arrangements of various segments remind of miniature paintings with characters that seem like kings and courtesans placed on some sort of flat space.

The method of making this kind of pictorial stuff is not only cumbersome in terms of its physical effort and limitations, it is also challenging to come up with a subject or composition of one’s own choice and preference. Like doodling, this technique can not be controlled easily and thus takes its own course. So it is remarkable that Malik was able to achieve what he wanted to portray with this material.

Perhaps the fascination or limitation of this medium is about its quality of line; line that does not exist in its virtual form on a sheet of paper or on a piece of canvas but has its undeniable and unavoidable physical presence. This physicality makes it difficult and dangerous to handle but offers new ideas and options for the artist. Quite astonishingly, in his new works, a few works are purely based on abstract forms, something that is not associated with the art of Afshar Malik.

This body of work still includes an element of joy and pleasure so typical of Malik, be it the painterly surfaces or layers of collages or intersecting and intricate textures fabricated with extraordinary care and craft. Yet, there seems to be an aspect of pain not only in the use and choice of medium but in presenting these hollow figures. The man who is playing on his pipe and saxophone (in ‘So Curios This Tale is’ and ‘Jugalbandi 2’) or a large woman surrounded by other smaller bodies (‘In the Shadow of Thick Affections’) or tribesmen with their distinct emblems (‘Deals and Deeds of Tribesmen’), all indicate how the artist likes to play, twist and transform his line, in order to formulate that complex pictorial synthesis which is simple on the surface in terms of reading and recognising figures, but uncommon in its lyrical and poetic characteristics.

This fondness and preference for personal usage of line and other elements marks and puts his work in a distinct league. Although the work at Canvas is imbibed with the same sense, it has been executed in the most unexpected technique with reference to Malik’s art. One may question the need to change his imagery and gauge its success on the basis of the sale of works, the artist’s decision to move away from his usual and expected set of visuals is a great leap into the unknown. So for many the new collection of works at Canvas Gallery may appear as not resolved or unnecessarily uniform in method and technique but, for a viewer familiar with the art of Malik and the art of Pakistan in general, it is a courageous move. Because it is more significant to transform; it is hardly important or relevant to know what that modification brings as its first crop since the seeds of change shoot up after several seasons and exhibitions.

Any similarity with the present Pakistani political situation is just coincidental!