No one has the right answer but everyone wants to avoid the wrong one

On the eve of August 13, 2014, it is safe to say that everyone was citing the Constitution to make their point. That is how Constitutions are used; a support pillar to gain credence or legitimacy for social, political and economic positions.

Patriotism and its rhetoric are similarly useful licenses to shame political opponents. The duties of patriotism have been invoked by the government as well as those marching on the capital. So who is right?

Instead of taking sides in matters of deeply-held political beliefs that divide people, there is a lot to be gained by engaging with each side’s perspective. The PTI’s Azadi March claims that it is for democracy. The dissenters say that the means as well as the potential ends smell of foul play. The PTI invokes the promise of the original bargain: participatory representative democracy. One man, one vote. The natural corollary of this is that each man’s vote counts. Hence the disgruntled vote-bank willing to raise the stakes. Imran is an ambitious and, equally importantly, ageing politician realising time is not on his side. He needs to push a system that has frustrated him for, in his eyes, far too long. To him it is obvious that this country needs him in-charge -- all ambitious men need some validation.

Jinnah needed it too.

On the other hand you have the prime minister. Mian Nawaz Sharif is a seasoned politician -- a man who has evolved and matured over the years. He has made a resounding comeback into the national imagination and politics. He has convincingly won an election. He joined hands with the late Benazir Bhutto Shaheed to take on a military dictator. For him, this is democracy’s glorious moment in Pakistan -- his ticket to a place in history for his struggle. He also cares deeply about democracy and therefore probably feels some concern for PTI’s naivete, as older uncles often do, when he sees the PTI hanging out with Dr Qadri.

For Sharif, Imran’s invocation of the original promise is misplaced. Fine, Sharif would say, Imran might have a problem with the election results but the constitution lays down a specific procedure of deciding election related disputes through particular tribunals. By demanding a sit-in till resignation of the PM over disputed election results, you are in murky territory -- a territory where the ever-ready revolutionary vanguard, the military establishment, and not the Constitution decides disputes.

Keeping in view Pakistan’s history, Sharif could reasonably argue that Imran is being irresponsible. Imran of course would argue that this is rich coming from the PML-N, considering its alliance with General Zia. The PML-N would shoot back that they have grown up and so should Imran. The debate could go on.

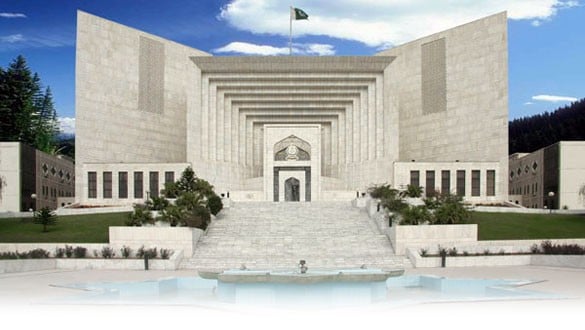

The courts got involved too. Was it unfortunate or necessary?

I sympathise with the view that a High Court should normally stay away from deciding essentially political disputes. So what should one make of the Lahore High Court order that restrained unconstitutional acts during or leading up to the Azadi March?

The answer is: smart positioning.

While the petition was being heard, the Honourable High Court’s questions revealed its deeply sincere concerns for law and order in the country. The PTI was asked if it would distance itself from Dr Qadri’s clear incitements to violence. The court asked if an ‘East Pakistan like’ situation was imminent, why should it not interfere?

The answer, of course, is that even a court ruling could not have stopped an East Pakistan.

When the tide of politics changes, everyone is swept away with it. Court rulings cannot prevent military coups or literal disintegration of states. In fact, courts are usually careful to give rulings in such matters to ensure that institutional credibility remains intact. In this case too, the High Court in a very mature fashion has shown two important things.

One is that in a country like Pakistan the courts cannot stay away from such disputes. Courts are forums of political dialogue between states and a dispassionate arm of the state. Hence some involvement will be necessary to achieve a careful balance. They cannot turn petitioners away.

The second important thing is that courts will stand for law and order -- and will not allow anyone to challenge the constitution. This is of course a mixed bag. If a coup does happen, a court cannot stop it since a court does not have an army. But the rhetoric of fidelity to the Constitution is important. It pervades a certain kind of important political discourse and the High Court was aiming to further it. It served a reminder to everyone that Pakistan is an evolving democracy -- a nascent one -- and we are all in this together. It rightly reminded Imran Khan and Dr Qadri that they should not throw out a system that everyone has tried so hard to rebuild.

Of course, some people will raise the argument that right to petition against a government and association is one of the basic political rights. That is indeed true. Protesting is a fundamental right and people throughout the world demand resignations from their elected leaders when they fail in their promises. Granted. But here is the difference between the rest of the world and what Dr Qadri and Imran Khan are saying: the country will have to be locked down if they do not succeed.

In fact, they go a step beyond and paint a picture of anarchy where law enforcement officials will be under threat unless the state succumbs to demands.

This enters a more murky territory. When you start exhorting people to hurt or kill policemen or political leaders, you might be exercising free speech but you are also inciting violent conduct: and must be ready to face the consequences.

The picture of anarchy cum revolution that Qadri and Imran Khan have painted with their rhetoric is the reason that everyone, including the courts, have been on the edges of their seats. The cost here is too great -- even the potential cost. The spectre of Pakistan’s own history haunts it.

No one has the right answer but everyone wants to avoid the wrong one.

There will be those who will argue that all great political movements have somehow challenged the existing order, i.e. pushed the constitution to its very limits. But the reason those movements were great and were able to get away with it was because they had the politics on their side.

India was carved up on August 15, 1947 not because the law demanded it but because the politics made any other solution practically impossible.

No one has the right answers here -- but let us hope we keep talking in our search to avoid the wrong ones. And, hopefully, we will ask important questions along the way, of ourselves and each other.