How do antithetical ideas like religion and nationalism pan out in Pakistan

An opportunity afforded to me to have an exchange of views with students by a local forum in Lahore was instructive indeed. As expected, the talk was followed by a marathon session of questions and answers but the questions raised by the young and extremely inquisitive audience opened some new vistas of perception.

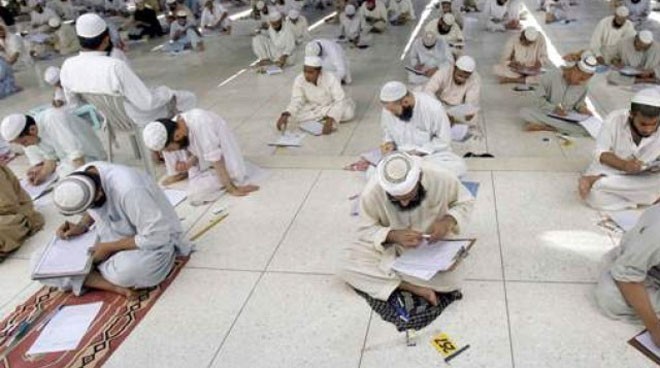

The theme of the talk was ‘Pakistan: Nationalism and Religion’. It was a thoughtful subject because both ideas, on a conceptual as well as historical development level, are antithetical to each other.

Nationalism and nation-state, notionally as well as historically, are European in essence. Adam Smith deployed the word ‘nation’ in his famous treatise ‘Wealth of Nations’ published in 1776. Concurrently, the nation-state system had its origin in the treaty of Westphalia, which was concluded in 1648, and has kept evolving up to its current stage. One may argue that the idea of the nation-state had become quite fixed by the last quarter of the 19th century.

In the course of its evolution, the nation-state as a political category and also in its practical configuration hardly invoked a religious sanction to validate a claim for its existence. One may even aver that the former prospered at the expense of the latter. The proponents of nationalism authenticated themselves by denouncing the infringement of the Christian Church in the political realm which was expounded to be the sole preserve of the state.

The antithetical position that the two phenomena -- nationalism and religion -- came to hold in Europe and elsewhere was turned on its head when the Muslim political elite staked a claim for a separate state in South Asia. The ideology underpinning of the struggle for Pakistan was punctuated by religion. Somehow, the Hegelian synthesis between the two ‘opposites’ failed to take effect in the case of Pakistan. Conceptually, the universal category of Umma/millat was the principal irritant.

After a few decades of its existence, we saw the Islamists upholding the cause of an ‘amorphous’ Umma to the detriment of the Pakistani state. The eventual preponderance of the ‘traditionalist’ version of Islam with a tangible Middle Eastern ring to it has overpowered ‘modernist Islam’. It will not surprise many if Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and Ameer Ali make an unceremonious exit from Pakistani textbooks because of their far too progressive interpretation of Islam.

The question pertaining to the tenuous relationship between religion and nationalism calls for serious and critical deliberation at an academic level so that some tenable and fresh conclusions can be drawn.

My talk emphasised on an alternative discourse to the established ideology which may help us to re-order our national priorities. By giving currency to various narratives, some space may be made available to minorities and other marginal groups and factions. Pursuing a singular ideology leads to an ascendancy of arbitrary if not outright fascist tendencies. For the sake of social and political advancement, multiple ideologies should be allowed to take root and flourish.

I found myself in a quandary when a question was asked about how an alternative discourse could be formulated and disseminated when rigidity has permeated to the very core of the social ranks of Pakistan. I did not have a ready answer to the question. In many other post-colonial states and societies, Marxist thought provided an alternative discourse. It was interpreted in varied circumstances and eventually some fresh social synthesis was brought into being. German philosophical development from the 1930s onward is a case in point. However, in the case of Pakistan, resorting to Marxism in our quest for an alternative discourse is more likely to be a self-defeating exercise because the Right’s propaganda has rendered anything even remotely associated with Marx irrelevant.

Perhaps, some headway could be made by encouraging our social scientists to produce knowledge by employing social tools of analysis. Such an exercise, if carried out in an academic fashion, should discredit unqualified assertions based on propaganda and slogan-mongering. In a bid to do that, the study of history and sociology has to be given primacy.

Besides, academics must assume a role as public intellectuals. Academics in both social sciences and humanities ought to feature prominently on television channels and come forward with their own prognoses. It may seem small but could be a crucial step in the right direction. Their absence in the print media is also quite stark. They are earnestly entreated to start pushing their respective pens for the good of society and the state. That would be one way of getting rid of those propagandists who have the gumption to comment on every issue under the sun -- from atomic bomb to any edict of Sharia.

By taking an academic view of the social realities of Pakistan, the possibility of some alternative discourse may sprout from within the prevailing discursive paradigm. Any ideology, if scrutinised afresh in the light of the cultural pattern entrenched in local ethos, is bound to create space for multiple narratives and social identities. The abstract ideology which is imposed from the above with utter disregard for indigenous realities will squeeze the space which is necessary for multiple ideologies.

That interaction with students and their unending quest for knowledge gave me a sense of equanimity and satisfaction. Heading home after the meeting, I kept ruminating and saying to myself that, despite all the problems, perhaps all is not lost.