BBC 4 and 3, unlike the other five hundred channels you can see in England today, are evening channels. Their programmes don’t begin until 7pm and close down at about 2am. And while BBC I and 2 keep struggling to fulfil their responsibility of being a public service broadcasting service, BBC 3 and 4 still persist in reflecting Sir John Reith’s belief that the aim of BBC is "to carry into the greatest number of homes everything that is best in every department of human knowledge, endeavour and achievement." This they do, thank heavens, without any regard to "ratings". The programmes that they screen -- apart from the lesser known works of classical and popular musicians -- range from the plight of slum dwellers of Indonesia to the amazing effects of fungi on plants and trees.

Last week I spent two whole evenings riveted to BBC 4 and learned more about the new biological discoveries than I have in my whole life. Why had it never occurred to me that Biology could be such a fascinating subject?

* * * * *

I first visited the sanctified halls of the Broadcasting House at Langham Place in London in 1953. The BBC was hallowed ground for anyone connected with broadcasting, as I had been in Sydney, Australia -- and even before in Lahore. The marbled, circular reception hall with its cathedral-like high ceiling and its fat, forbidding columns and the hush that prevailed, (broken every now and then by the silky voice of the receptionist summoning one of the many livered guards to escort Mr Willoughy Goddard or Mr Allardyce Swinton to the inner sanctum), created a sense of absolute awe.

I sat there for quite some time before I was taken to see J.B. Clarke, the Head of Drama, I tapped the inside pocket of my jacket for the umpteenth time to make sure that I still had the letter addressed to him, given to me by ZAB (Zulifqar Ali Bokhari, the Director General of Radio Pakistan) who had known Clarke since the days they were both young producers -- Clarke, in the talks department, and ZAB, in the BBC Overseas Services during the War years.

Clarke read ZAB’s letter in which I had been described as a talented young broadcaster as well as this, that and the other. He chuckled over it, ordered some coffee and told me that the BBC was a fustian organisation. "We’re rather Reith ridden over here." Then, realising that I didn’t know what he was talking about, he told me the famous story Reith’s detractor had ascribed to him.

Reith was once walking the corridors of the Broadcasting House when he met Jesus. He asked Jesus what he was doing there. Jesus explained that he had come to deliver the epilogue (In those days the BBC ended its nightly transmission with an epilogue spoken by some eminent man of the Church).

Sir John Reith demurred in some embarrassment. "I’m afraid not," he grunted "there was always some little doubt about your mother".

* * * * *

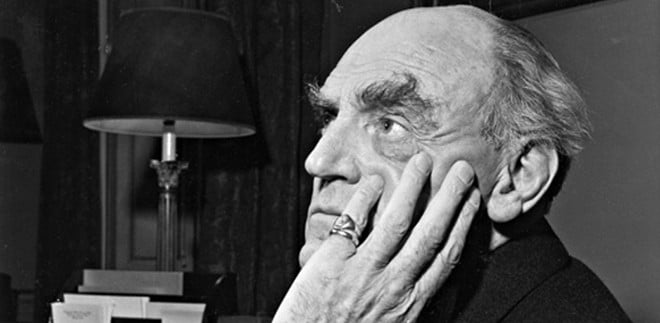

Reith was the son of a fiery preacher from the fundamentalist Scottish Presbyterian Church, who took a profoundly serious view of life shunning all worldly pleasure and demanding that his son does likewise. John Reith imbibed the puritan message but he was also prone to rebellion. Hallam Tennyson, a senior BBC producer, told me once that Reith was a terror in the corridors of the BBC. Everyone quailed in his presence. He allowed no laxity in the morals of his staff. Unfortunately he spectacularly failed to implant those values in his own life.

The architect of the BBC, Lord Reith has been the subject of more than one study. Reith had worked as a reputable engineer in England and America when he was appointed by the government in 1922 to be the first manager of the British Broadcasting company at the start of the Radio revolution. His organising skills and his qualities of leadership enabled him to transform the BBC from a fledgling radio company into a mighty global institution. As the first Director General of the Corporation he presided over a huge expansion in the workforce and the scope of operations, including the World Service and introduction to television.

In his book The Last Victorians -- A Daring Reassessment of Four Twentieth Century Eccentrics, Sidney Robinson reveals that Reith had a grandiose vision of himself as a kind of heroic Napoleonic genius. "He became an egocentric monster, obsessed with his own advancement, prone to volcanic bursts of temper and profoundly embittered if he did not receive the recognition he felt he deserved."

Robson tells us that Reith got bored with the BBC and hankered after other bigger roles for himself including the viceroyalty of India. He left the corporation in a fit of pique in 1938 and took on a series of unfulfilling assignments which he thought were beneath his exalted ability. He was not chosen as the Viceroy of India, but he did become the Minister of Information in 1940. He sought a higher position for himself in Churchill’s wartime government but Churchill did not approve of him.

Reith hated Churchill so much so that even after the War he referred to Churchill as ‘an imposter’, a ‘menace’ or simply ‘that S**t’. "It will be a hundred years before Britain gets over the malign influence of the unscrupulous man", he said to a friend in the bar of the House of Lords, while Churchill’s body lay in state in Westminster Hall.

In the post-war years Reith developed a sense of loathing of the BBC. According to Robson he refused even to watch television or listen to the Radio. He dubbed some of the programmes on television as ‘evil’ while the ‘vulgarity’ of the Radio Times made him feel sorry that he ever started.

In his old age he was barely able to fend for himself and survived on a diet of biscuits, bananas and marmalade. But egocentric in life he was modest in death ordering that there be no eulogy delivered at his Spartan funeral service. His final instruction was that his ashes should be placed in a ruined highland churchyard where only the wind could listen.

According to Robson part of the difficulty lay in Reith’s tortured sexuality. He was drawn to young boys. In today’s climate, when so many eminent politicians are being accused of having troubling infatuation with children and adolescents, Reith would have been dubbed as a paedophile and hauled over the coals.