Apart from their distinct quality of language, Ghalib’s letters present a largely new way of looking at individual and collective life

What constitutes ‘literature’ is a loaded concept in the context of Urdu, deeply entangled with the politics of collective identity which informs our lives in the most fundamental ways. While defining its literary canon, Urdu’s cultural and political decision-makers managed to deny a large part of its historical, local identity. As the choice of what ‘should’ be included was dictated by the political expediency of defining ‘Urdu’ as the other of ‘Hindi’, we observe large gaps in the history of the development of Urdu language and literature as recorded by its myopic historians. We see with wonder that Kabir and Mirabai are not considered the pioneers of the Urdu poetic tradition; Nazeer Akbarabadi is disliked by the elite historians and critics for his fascination and celebration of local forms and content.

The main thrust seems to be to exclude or suppress the local and privilege the ‘imported’, to create an illusion that we, the North-Indian Muslims, are somehow immigrants from a foreign land and not converted locals which we in fact are. The political need to make Urdu look like a special language specially manufactured by and for a few influential Muslim communities of the land forced its elite to make some foolish and dangerous choices as a result of which Urdu has been all but reduced to not just a Muslim but a Deobandi/Salafi language.

The most recent trend has been to mindlessly link it to the tongue of the Saudi kingdom, taking the ongoing cultural denialism to an even more absurd level.

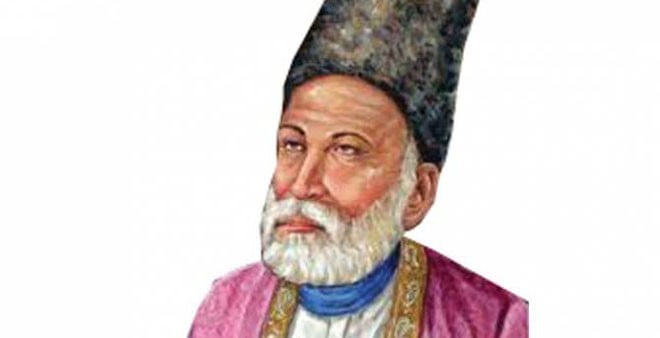

Urdu was fortunate to have Ghalib at the juncture of a great political, social and cultural transformation in the life of North India. His literary oeuvre not only shows him as one of the harbingers of cutting-edge modernity among the local elites, his literary and cultural choices seem to sometimes run at odds with those of the elite he belonged to. Not only did Ghalib indicate the need to expand the horizon of Urdu poetry beyond the limited scope of ghazal, in his personal correspondence a conscious literary effort can be seen to devise a new prose that could express the local, the immediate and the everyday content of human life. Without his contribution it is hard to imagine that Urdu prose could have become what it did some sixty years after Ghalib’s demise.

It is not just this distinct quality of language, as against the highly stylised prose of the dastaans created to eulogise the privileged pastimes of the various Muslims invaders/rulers, that makes Ghalib’s letters a celebrated part of the Urdu literary canon; these letters present a largely new way of looking at individual and collective life. While the entrenched formal ‘tradition’ of Urdu prose of his time made too much of the conquests of ‘infidel’ lands and peoples, and took the rise and fall of Muslim kings and nawabs rather too seriously, Ghalib introduced in his correspondence a great penchant for informality and a living current of irony, humour and satire. Even when talking about personal misery, bereavement and social chaos, he was capable of steering clear of sentimentalism and a false sense of being above others.

Ghalib records with awe and admiration in one of his letters the occasion when the British colonial hakim (ruler) of Delhi was peacefully replaced by his successor an occurrence totally against the norm of the local feudal aristocracy and the political history they attached themselves to, according to which it was considered necessary for a successor/heir to neutralise all possible claimants to power or property before he could establish himself. This admiration on Ghalib’s part is of a piece with his appreciation of the technological fruits of the industrial revolution - it can legitimately be read as the precursor of a felt need for a modern, more equitable, more inclusive, non-violent social order.

That Ghalib’s personal correspondence had to be included in the canon of ‘high literature’ even by the essentially conservative and backward-looking literary elite was a proof of its literary vitality which successfully changed the course of Urdu prose literature. As for his inquisitive outlook, alive to the changing times and human progress, unfortunately it could not become the mainstay of the larger literary and political culture of Urdu and Urduwalas, thanks to the retrogressive path forced on us by successors who insisted that revival of the old, harmful values must be our fate.

Although Iqbal - the next literary ‘great’ in the context of Urdu - fulfilled Ghalib’s desire to find wider horizons of Urdu poetry in terms of form, and finished off ghazal’s dominance once and for all, he patently lacked Ghalib’s vision for a new social order. Iqbal, on his part, invested his energies in the project of ‘revival of Islamic kingdom’ instead of guiding his readers to a modern way of life.

This is a web exclusive article and did not appear in the print edition of The News on Sunday.