It is time to turn to literature or poetry, to see how others have felt and expressed and dealt with their sorrows -- through writing.

Dear readers,

We hope you’re doing fine.

We know these are not easy times. There ought to be a limit to the sad stories one is fed day in and out, after all.

We understand that a landlord chopping off a young boy’s arms, a crowd setting on fire a community that the majority sect has declared non-Muslim and killing its women and children, or just watching images of dead and injured Palestinian children and their tearful parents and siblings, is just too much for a sensitive person to handle.

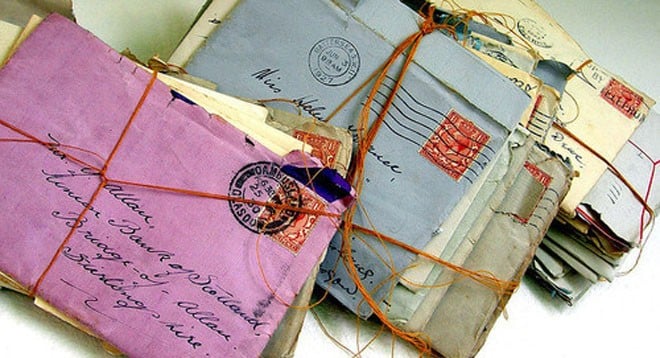

It is time to turn to literature or poetry, to see how others have felt and expressed and dealt with their sorrows -- through writing. Sometimes, these writers and poets wrote it in the form of letters. Often, they have done it so well that their letters attained the status of literature.

This week, we bring you just a taste of what some of these letters by famous men and women could achieve in their very personal communication. At least in one case, that of Franz Kafka’s outpouring to his father (reproduced below), the letter was not even sent.

These letters belong to another age, and yet the human concerns -- joys and sorrows and what not -- look so familiar. So we can’t guarantee we are taking you away from life; just a little away from the immediate pain and anguish, and a little near to pleasures of writing.

You asked me recently why I claim to be afraid of you. I did not know, as usual, how to answer, partly for the very reason that I am afraid of you, partly because an explanation of my fear would require more details than I could even begin to make coherent in speech. And if I now try to answer in writing it will still be nowhere near complete, because even in writing my fear and its consequences raise a barrier between us and because the magnitude of material far exceeds my memory and my understanding.

To you the matter always seemed very simple, at least in as far as you spoke about it in front of me and, indiscriminately, in front of many others. To you it seemed like this: you had worked hard your whole life, sacrificed everything for your children, particularly me, as a result I lived "like a lord", had complete freedom to study whatever I wanted, knew where my next meal was coming from and therefore had no reason to worry about anything; for this you asked no gratitude, you know how children show their gratitude, but at least some kind of cooperation, a sign of sympathy; instead I would always hide away from you in my room, buried in books, with crazy friends and eccentric ideas; we never spoke openly, I never came up to you in the synagogue, I never visited you in Franzensbad, nor otherwise had any sense of family, I never took an interest in the business or your other concerns, I saddled you with the factory and then left you in the lurch, I encouraged Ottla’s obstinacy and while I have never to this day lifted a finger to help you (I never even buy you the occasional theatre ticket), I do all I can for perfect strangers. If you summarize you judgment of me, it is clear that you do not actually reproach me with anything really indecent or malicious (with the exception, perhaps, of my latest marriage plans), but rather with coldness, alienation, ingratitude. And, what is more, you reproach me as if it were my fault, as if I might have been able to arrange everything differently with one simple change of direction, while you are not in the slightest to blame, except perhaps for having been too good to me.

This, your usual analysis, I agree with only in so far as I also believe you to be entirely blameless for our estrangement. But I too am equally and utterly blameless. If I could bring you to acknowledge this, then -- although a new life would not be possible, for that we are both much too old -- there could yet be a sort of peace, not an end to your unrelenting reproaches, but at least a mitigation of them.

--Franz Kafka