Provinces should resist attempts by the federal government to mutilate the gains of the 18th Amendment especially its vision of a uniform curriculum

In the post-18th Amendment scene, education has been devolved to the provincial governments. This was one of the achievements of the PPP government that went overall unacknowledged and the results of the 2013 elections displayed a general displeasure of the masses with the PPP. Irrespective of the poor performance of the previous government, the 18th Amendment remains a hallmark of democratic legislation with which almost all political parties tried to correct the wrongs of the previous decades.

Education is one such subject that has come to mean a lot for the provincial governments and despite the attempts of the new PML-N government to undo some of the changes, the provincial governments -- other than Punjab -- have expressed their desire to continue with the devolved ministries without surrendering any of the authorities given to them through this amendment.

Though it is possible to remain content with just devolution on paper, one has to admit that the provincial governments have done little to take full advantage of the devolved authority, especially in terms of curriculum development. Recently, in one of the seminars, the federal minister for education (the name of this ministry has been changed so many times in the recent past that it is better to just call it ministry of education here) outlined his ideas about a uniform curriculum for all the provinces.

The idea of a uniform curriculum seems innocuous at the outset but if you look at it in perspective of what the various federal governments have been doing during the past seven decades, it becomes clear that the repeated attempts to project Pakistan as one-nation state have failed miserably. In fact the federal government has been playing havoc with the curriculum.

First, official historians such as IH Qureshi, during the Ayub Khan regime, tried to present a sanitised version of history to students. In this version, most of the Muslim kings and rulers were projected as god-fearing and religion-promoting zealots.

Second, during General Ziaul Haq’s devastating 11 years, Pakistan Studies assumed an all-encompassing subject excluding geography, history, and social studies. Now the focus was on people such as Mujaddad Alf Sani, Shah Waliullah, Syed Ahmed Shaheed Brelvi, and other religious personalities at the cost of more liberal and forward-looking reformers such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and Syed Ameer Ali. Anti-Hindu bias became so prominent in the government prescribed textbooks that students could hardly think of them as normal human beings.

This excessive religiosity and bigoted presentation could have produced only a prejudiced and narrow-minded young generation. The fallout of which we are witnessing in its extreme form now.

Third, the real heroes of this land were never given any space. For example, pupils do know about Sirajudaullh and Tipu Sultan, but how many are familiar with freedom fighters such as Sardar Mehrab Khan of Balochistan, Hosh Muhammad Shedi of Sindh, Ahmed Khan Kharal of Punjab, and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan of the Khyber-Phakhtunkhwa? While the textbooks in India include many Muslim freedom fighters, the textbooks in Pakistan do not even include those prominent Muslim personalities that were not supporting Muslim League. Such Muslim personalities, despite their tremendous sacrifices in the freedom struggle, are projected in a highly negative colour which is contrary to all good curriculum making practices.

Fourth, the post-independence history is replete with the tales of incompetence of political leaders and with achievement sagas of army personnel. Usurpers, such as General Ayub Khan and General Ziaul Haq are projected as saviors of the nation. Even the most important event of the post-independence history i.e. the Fall of Dhaka barely deserves any mention in our school textbooks. The separation of East Pakistan is presented as the culmination of conspiracies hatched by Bengali traitors and who else but Hindus.

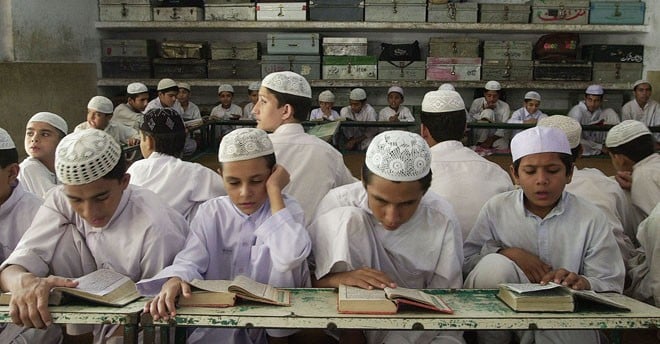

So now, what should the provinces do? First of all, they should resist the attempts by the federal government to mutilate the gains of the 18th Amendment. The arguments in favour of a ‘uniform curriculum’ are flimsy, to say the least. There are already dozens of curricula being used in the country -- in private schools run by various foundations, in madrassas managed by colourful religious outfits, in cadet colleges established to produce overly patriotic and pro-establishment graduates, and in non-formal schools catering to the needs of the marginalised segments of society.

The curricula for subjects such as English, computers, math, and science are almost the same the world over. If you pick a book of math being used in grade seven in China or in the USA, the topics covered will be all but similar. It is the presentation of these topics -- and the exercises used to clarify these topics -- that makes the difference. It is the teaching methods and the supplementary materials that put them apart; the learning environment and critical thinking distinguish good education from bad one; and most of all it is the encouragement of multiple perspectives and nurturing of a curious mind that create a learning society and not uniformity and submission.

Contrary to the established narrative of promoting English and Urdu as the sole ladder to success, a narrative of understanding should be espoused. It is an undisputable fact that early learning comes easiest in one’s first language i.e. the language one is most exposed to from early days. Concept clarity should be at the centre of all curricula, and if this point is understood the regional languages stand out as the most suitable medium of instruction, especially at primary stage.

Since most of the decision-makers in the education ministries are neither educationists nor do they have any inkling about the importance of critical thinking and diversity of thought, it is likely that the newly-won devolution will fail to deliver any fundamental change in education status unless the provincial governments initiate a process of thorough review of the curricula especially regarding history and social studies.

There is a need to teach post-independence history with a view to highlight the sacrifices made by political leaders and intellectuals to make Pakistan a democratic and tolerant country. Chapters should be included about personalities such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Mian Iftikharuddin from Punjab, GM Syed and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto from Sindh, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan and Mufti Mahmood from KP, and Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizinjo and Akbar Bugti from Balochistan. This list is not exhaustive and many more names can be included in curricula for various grades.

The point is to give a fresh look to the narrative being imparted to students. The prevalent anti-democratic and intolerant narrative has produced disastrous results and there is a dire need to unplug the supply of hatred and bigotry so that the new generation is able to see and understand that a democratic society does not persecute minorities and people belonging to other religions and sects are not devils.

Evil is not believing in a particular denomination; it is in the belief that one’s own creed is superior to all others. There is little hope from the federal government to change this narrative. Now it is up to the provinces to take the lead and cultivate the seeds of diversity and nurture the cornucopia that our country is.