Need for implementation of labour standards in football industry came to the fore in November 2006 when global sports brand -- Nike -- cancelled its order of hand-stitched balls to its contracting manufacturer, Saga Sports Private Limited. The decision was taken by Nike when it was convinced that its supplier was violating labour standards and employing child labour.

According to a study carried out by Pakistan Institute of Labour Education and Research (PILER), Saga Sports had a workforce of 7,637 people when this order was cancelled. Of these, 5,257 people were piece-rate workers, residing in more than 400 rural settlements dispersed in three tehsils of the district-Sialkot, Pasrur, and Daska.

Under the piece-rate agreement, workers are paid per football they produce and not paid a fixed salary. It is believed that such agreements deprive workers of their right to take rest or leave with pay, get a medical cover when they are ill and unable to work, receive a fixed income even when there are no orders to fulfill and to get overtime at double the normal rate if they work extra.

After the cancellation of the agreement between Nike and Saga, factory owners claim they have taken measures which have led to improvement in the situation. Still, independent observers believe a lot more needs to be done.

At the same time, labour rights activists accuse the industry of taking cosmetic measures to show it to the world that things are moving in the right direction. But they believe that they cannot secure and increase their share in global exports if they fail to convince to the world that they are not exploiting labour to their benefit.

Khalid Mahmood, Executive Director, Labour Education Foundation (LEF) tells TNS that he has recently talked to workers at Forward Sports, the company which has supplied Brazuka balls to Adidas. These workers, he says, confirm the claim of the company’s CEO Khawaja Maqsood Akhtar that he has paid them Rs 10,000 -- the minimum wage fixed by the government.

But Mahmood believes this amount is fixed for unskilled worker and should not be taken as standard wage. "The workers employed at football production units are highly skilled and should be paid more than double this amount," he demands.

Mahmood says he regularly visits Sialkot and meets workers employed by different companies. During these visits, he has observed that very few companies register their workers with the social security department. Trade unions are few and only on paper. A few units have dispensaries which lack medicine and competent medical staff and paramedics to take care of workers’ health. "It seems they have been set up just to attract global brands who are highly concerned about workers’ safety at their workplaces," he says.

While Pakistan is celebrating the achievement of supplying official world cup footballs, there are critics who say the country received these orders because the cost of production had risen in China and Pakistan could provide them at lower rates.

Aziz-ur-Rehman, Director Sourcing, Adidas, in Pakistan rules out the perception, saying labour cost is never a big consideration in production of high-end products. The chances of labour right violations, he says, are high when the main objective is to produce low-cost products. The original Brazuka football is up for sales at rates as high as 140 euros at stores around the world.

He tells TNS that global brands, including Adidas have their own monitoring systems to ensure that labour standards are implemented in factories working on their orders. "The reason why Forward Sports was selected as a supplier by Adidas," he says, "was that it was already working with the company at a certain level. Besides, Forward Sports volunteered to supply these footballs within a short timeframe when the Chinese factory engaged by Adidas expressed its inability to complete the orders in full. "The shortfall was covered by this Pakistani company on a short deadline."

Tariq Awan, Field Coordinator at PILER Pakistan, says child labour is hardly employed in the football industry in Sialkot. "One major reason for this trend is that demand for hand-stitched footballs has come down due to popularity of machine-produced balls."

However, he says, "the sports goods manufacturers are not willing to allow their workers to form unions, get them registered with social security department and EOBI, and pay approved piece-rates to workers as announced in the gazette notifications issued by the government from time to time. There are different rates for painters, stitchers, laminators, etc, but the minimum approved rate is applied on all."

According to Awan, PILER had a meeting with Sialkot Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SCCI) a couple of years ago on the issue of social security cover for workers and permission to workers to form unions. The owners said they could not allow unions as they considered them anti-work and that they could not pay social security contribution to the government.

The owners were of the view that since they were paying Export Development Fund (EDF) to the state, the government should deduct contributions against social security and EOBI from that amount. Other issues that came to the limelight during the visits were about workplaces being cramped with no exhaust system.

Awan is skeptic about monitoring mechanisms adopted by foreign buyers, which he says have done little to improve lives of workers. He cites the example of the garments factory in Baldia Town, Karachi, which caught fire, leading to death of hundreds of workers. "The factory was inspected for labour safety only days ago and certified by an international company to be fully safe. What followed puts a question mark on the competence and credibility of such organisations and the utility of carrying out such exercises," he adds.

The SCCI spokesman, Tajammal Hussain, says most of their member companies are complying with national and international obligations regarding assurance of labour rights to their workers. In case there are disputes between workers and employers, they are brought to the notice of the chamber office-bearers who try to solve them amicably through deliberations and consultations. He agrees that there are companies that violate labour rights and suggests that the good ones should not be bracketed with the bad ones.

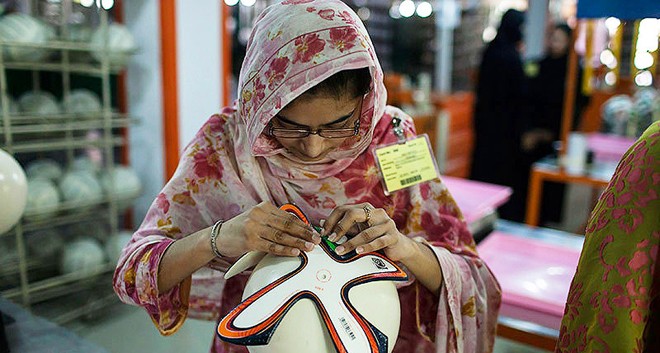

On the existing practices in the football manufacturing industry, he says the new generation which his highly skilled in football making sign contracts with companies to supply the decided quantities of footballs at a mutually agreed rate within a particular timeframe.

In such cases, it is up to the contractors to engage households in work and determine their wages, workers hours, etc. The government and the industry cannot intervene as this activity goes on in an informal sector of economy.