The two-day conference titled ‘Pakistan: Creation and Consolidation’, organised by the Department of History, Forman Christian College, in mid April 2014, brought together a myriad of perspectives on the subject. While the subjects and merits of each paper are discussed below (and in the previous article), the conference showed how little engagement is there with the first few decades of Pakistan.

It clearly exhibited how critical the first decade was in Pakistan -- especially leaving an indelible mark on issues like, national identity, the balance between centre-province relations, institutional authority and linkages, foreign policy persistence and the economy. Further research into these issues will not only enable us to understand the period better, but as several panels clearly exhibited, will help us grapple with these issues (and they strangely remain the same!) today. This conference was a small attempt in stirring up academic discourse in Pakistan, and I hope it has done its job.

Panel four was on the issue of ‘Provinces and Region,’ an issue which still festers in Pakistan. Here Professor Sarah Ansari, Professor of History at Royal Holloway, University of London, and an expert on Sindh, spoke on the ‘Politics of Numbers’ in Sindh after independence. She argued that soon after independence ‘numbers’ became an important aspect of the centre-province relationship.

She pointed out how the rehabilitation of refugees, reservation of jobs, provision of government services, etc., all were contested on the basis of numbers in Sindh. In fact, an important aspect of the Muhajir vs Sindhi tussle has to do with the disputed ‘numbers’ each side claims. Obviously this ‘politics of numbers’ did not remain an issue entirely for the Sindh province; in later years, concerns over numbers have prevented governments from carrying out the census. After 1981, the last time Pakistan has a decennial census, it was delayed for 16 years, and now even after 17 year since the last one in 1997, no census plan is within sight.

Professor Willem van Schendel, Professor of Modern Asian History at the University of Amsterdam and an authority on East Pakistan/Bangladesh, then read his aptly titled paper ‘Forgotten Bengal: the Creation of Pakistan in the East.’ Indeed today mention of East Bengal (later East Pakistan) is almost ‘lost’ in the narrative of Pakistan, and people simply forget that it formed a part of Pakistan for about 23 years.

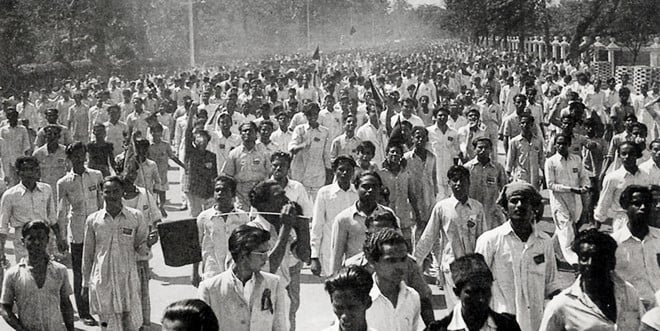

Professor Van Schendel spoke about the attempts of West Pakistanis to create a ‘Pakistani society’ in the East and how it immediately alienated the East Pakistanis. Subtly suggesting that the Bengali language was too ‘Hinduised’ and therefore unsuitable for Pakistanis; that ‘Hindu looking’ people were usually foreign spies; and that the typical Bengali lifestyle needed to be more ‘proper’ and ‘Muslim,’ were attempts with which the West Pakistanis tried to ‘reform’ and integrate the East Pakistanis. Obviously these moves backfired and a strong nationalist movement started in East Pakistan against these interventions.

The ways and means through which the West Pakistani establishment tried to change the Bengali culture were eye-opening as they targeted almost every aspect of Bengali life. Here one must wonder how a ‘national’ identity -- since that is what the West Pakistanis were trying to create -- is forged. Is it created by forcible adoption of an ‘ideal’ culture and identity, or is it the sum of all the cultures and identities present in the country? That is a question Prof. Van Schendel asked concerning East Bengal in the first decade after independence, and this is something we are still wondering about in Pakistan!

Professor Fazl ur Rahim Marwat, Vice Chancellor of the Bacha Khan University in Charsadda, was supposed to speak next on the "Challenges of the 1940’s in British India and its impact on Pakhtunkhawa," but he was suddenly taken ill enroute to Lahore and could not make it. However, he did send his presentation which was then shared with the conference attendees. In it, Professor Marwat traced the different trajectory of the Muslims of the erstwhile NWFP where they did not repose their political trust in the All India Muslim League but aligned themselves with the Indian National Congress through the Khudai Khidmatgar movement led by Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan).

Professor Marwat pointed out that even though the Pakistani authorities dismissed the democratically-elected government of Dr Khan sahib in late August 1947, the Khudai Khidmatgars still did not react but considering that Pakistan was going through a ‘critical stage’ resolved to work wholeheartedly for the development of the country. However, the Pakistani establishment did not believe that the Khidmatgars supported the country and, therefore, embarked on a relentless persecution regime where Bacha Khan and his associates were jailed for decades without any proven charges. Professor Marwat argued that since the creation of Pakistan, Pakhtun response to Pakistan has oscillated between cooperation and confrontation, but that a lack to appreciation of the Pakhtun life and culture, and the neo-imperialist policies of the establishment (especially using Pakhtun people and areas for the jihadis) have created deep fissures in the Pakhtun society.

I spoke next on the relationship between Balochistan (including British Baluchistan, and the princely state of Kalat and its vassals), and Pakistan during the first decade after independence. In the paper, I pointed out that the ruler of Kalat State, Mir Ahmed Yar Khan, wanted to remain independent after the Transfer of Power in August 1947 but the geopolitical conditions of the time and extreme pressure from Pakistan induced him to accede to Pakistan in March 1948, much to the chagrin of his tribal sardars who argued that the accession was invalid as they had not been consulted.

The first Baloch insurgency, thereby, began in June 1948 led by the younger brother of the Khan, Prince Karim, which, while it ended in disaster, sowed the seeds of lasting enmity between the Baloch and the state of Pakistan. A decade of tense relations between the centre, the states and the provinces, including the merger of the princely states in the one unit, further exacerbated tensions. The presence of non-Baloch civil servants and military personnel, even if for purely technical and logistical reasons, then began to be looked upon suspiciously by the Baloch further heightening tension.

The onset of martial rule in October 1958 was also blamed on the Baloch and their Khan, which led to another revolt in the aftermath of military action against the Khan. All these events, I argued, sowed the seeds for mutual distrust and antagonism which remain at the core of the Baloch insurgency today.

The next panel investigated the role of institutions -- the military, bureaucracy and Pakistani’s foreign allies, and their role in the early decades of the country. Speaking on the judiciary, Professor Osama Siddique from LUMS argued that the judiciary played second fiddle to the military and the bureaucracy in the post-independence period. Focusing more on its current implications, Professor Siddique pointed out that ‘Law Reform in Pakistan attracts such disparate champions as the Chief Justice of Pakistan, the USAID and the Taliban. Common to their equally obsessive pursuit of ‘speedy justice’ is a remarkable obliviousness to the historical, institutional and sociological factors that alienate Pakistanis from their formal legal system.’ He then highlighted the ‘vital and widely neglected linkages between the ‘narratives of colonial displacement’ resonant in the literature on South Asia’s encounter with colonial law and the region’s post-colonial official law reform discourses.’

Speaking on the bureaucracy during the first decade of Pakistan, Professor Ilhan Niaz from Quaid-e-Azam University argued that ‘overt military involvement in politics and policy-making, which became evident by 1954, did not automatically lead to the militarisation of the state apparatus and that in fact the 1950s saw considerable institution-building and strengthening on the civilian bureaucratic side.’

Relating it to the current situation, Professor Niaz stated that ‘without rehabilitation of the civilian bureaucracy, genuine rollback of military influence in society, economy, ideology, and administration, will prove elusive…and [that] such rehabilitation will require Pakistan’s civilian leaders to counter-intuitively reduce their powers over civil servants and adopt a less arbitrary mode of personnel management.’ Dr Ayesha Siddiqa was supposed to speak next on the military, but she had to cancel at the last minute due to a family emergency.

Commenting on Pakistan’s foreign policy, Professor Ishtiaq Ahmed, currently the Quaid-e-Azam chair at the University of Oxford, connected Pakistan’s early uneasy relationship with both India and Afghanistan, with its current foreign policy preoccupations. This ‘persistence’, Professor Ahmed pointed out, has kept Pakistan saddled with limited foreign policy options and has prevented better relations with not only its neighbours but also with the rest of the world. Professor Ahmed, therefore, called for a rethinking of Pakistan’s foreign policy paradigm and for a moving away from the preoccupations from the time of its creation.

The last panel featured distinguished scholars on the most important part of any country -- its economy. Analysing the creation of Pakistan from and economic perspective, Professor Imran Ali argued that ‘an entirely revised interpretation of the creation of Pakistan emerges from the contradictions and reactions that growth generated in this region, and that indeed these constituted a continuum of tensions embedded through the colonial and even late Mughal periods.’ He pointed out that if we look beyond political history we would realise that ‘the unease of Muslim elites over competition and mobility by emergent Hindu professional groups in the Gangetic plain apparently gave rise to the notion of separatism among Indian Muslims.’ Such an examination of the political economy of the creation of Pakistan is lacking, Professor Imran Ali argued.

Taking the discussion further, Shahid Javed Burki pointed out how ‘many of Pakistan’s structural features we notice today began to appear in the first post-independence decade.’ He argued that the political and economic decisions of the first decade -- for example not devaluing Pakistan’s currency when almost every Commonwealth country had devalued -- left a deep impact on the country’s economy. Flawed planning and structural constraints also stymied growth in this period.

Bringing the discussion full circle, Professor Akmal Hussain argued that ‘the tendencies for slow growth, high budget deficits and growing poverty, which were manifested in the eruption of an economic crisis in Pakistan during the 1990s, are rooted in the structure of Pakistan’s economy.’ He pointed out how ‘how various military regimes laid the structural basis for the deterioration in both the polity and economy of Pakistan, [and] how the various democratically elected regimes not only sought authoritarian forms of power within formally democratic structures but also accelerated the process of economic decline.’

Professor Hussain further argued that Pakistan currently suffers from the twin problems of weak institutions and failed leaders, which further exacerbate its economic tensions.

Read the first part of the article here