Professor Waseem’s brief sojourn to the University of Cambridge, UK, and his talk to graduate students at the Centre of South Asian Studies triggered a meaningful debate. While dwelling on the theme, Pakistan: A Fractured Polity, he said that ‘cultural separatism’ which took effect in tandem with ‘political separatism’ was orchestrated by the Muslim elite (ashraaf) of North India.

In the question-and-answer session, the professor was asked about the nature of cultural separatism for which the Muslim ashraaf of North India were being impugned. In response, he alluded to the project of Persianising of Urdu by the likes of Imam Bakhsh Nasikh (1776-1838).

He also underlined the increasing social segregation among the Muslim elite through practises like the sudden suspension of matrimonial relations etc. The fact that needs to be highlighted here is the gradual vanishing of what Prof. Dhruv Raina thinks, the ‘cosmopolitan elite’, an eclectic social category that has absorbed many semantic resources and also cultural practices.

Intriguingly, in Pakistan, the processes of cultural separatism had been considered the sole preserve of academics dealing in Urdu language and literature -- because the cultural particularity of Muslims was measured only through Urdu. More often than not, the practitioners in Urdu employed a primordial-essentialist approach to define culture through the prism of religious ideology, leading to nothing but cultural confusion.

That probably was the reason for hardly any attempt to map the cultural divergence which has lead to separatism.

The saga of cultural separatism commences, as reported in Pakistani textbooks, from the Urdu-Hindi controversy in 1867 at Banaras. That was meant to be merely an expression of the cultural separatism which was inherent in the North Indian social landscape.

One ought to be beholden to Tariq Rehman for unravelling the lingual-scriptural dimension of North Indian culture. His critical insight on the politics of language is laudable.

Prof. Waseem balked at mentioning the British as a factor contributing to the sharpening of cultural identities which, eventually, resulted in mutual exclusion. He does not subscribe to Nicholas Dirks’ or Bernard Cohen’s viewpoints, who placed a heavy onus on the British for reconfiguring the cultural identities of the colonised. Practices like the standardisation of languages, dialects or cultural patterns swept away the fuzziness which had so far held together culturally variegated demographic units.

The onset of modernity and its interface with indigenous social trends and practices gave rise to cultural divergences. However, certain actions and initiatives of the British officials are extremely important, for example, Sir Anthony MacDonnell, Lieutenant Governor of North Western Province, issued ‘the fateful order’ on April 18, 1900, allowing the permissive -- but not exclusive -- use of Devnagari in the courts of the province.

One may surmise that Altaf Hussain Hali’s Hayat-i-Javed has made that reference to MacDonnell who is projected as a demonic figure, despite the fact that he did not disallow the use of Urdu in the courts of the province.

That narrative resonates explicitly in Pakistan Studies books from the 1980s onwards.

MacDonnell is subjected to censorious treatment in the Pakistani mainstream educational discourse, and yet no mention is generally made of the policies carried out by the British whereby linguistic difference was played out in a manner that had far reaching repercussions -- particularly the "vernacular question" in the 19th century India and the way it was handled by the Court of Directors of the East India Company in 1832 needs to be reflected on to make sense of cultural/lingual exclusion. The policy directive was categorical in flagging it as essential that "justice be administered in a language familiar to the people at large…".

The consensus forged among the Court of Directors was that "it is easier for a judge to acquire the language of the people than for the people to acquire the language of the judge." It was that policy objective to replace Persian with the local vernaculars in the territories under company administration that unleashed the profound cultural dynamic that would work its diverse way for the rest of the century and far beyond.

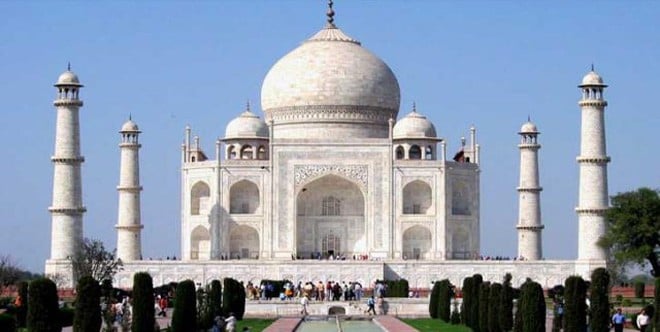

In the debate on cultural separatism, other modes of cultural articulation like music, painting or architecture and the commonalities and divergences emanating from them, have been completely erased from popular memory. Pakistani educational discourse does not address the essential nature of these art forms and also their current state is indicative of cultural separatism that is practised and professed across the border.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Mehdi Hassan, Noor Jehan and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan have a large following in India. Similarly, how come the architectural style that Nayyar Ali Dada has given currency to, is different from what we see in North India.

It is, therefore, argued that North Indian culture, even to this day, is fundamentally Muslim. The ideas and works of luminaries like Shibli Naumani, Altaf Hussain Hali and Hasrat Mohani, as Ali Khan, an upcoming Cambridge scholar clearly shows in his brilliant research, are embedded in the soil, by which they mean North India, which they considered as their watan.

Earnest academic consideration is required into the possibility of any nation-state like Pakistan to unequivocally adhere to its cultural ethos which it shares with other states (like India), without compromising its political and economic sovereignty.

Reverting to what Prof. Waseem mentioned while in conversation with graduate students, I will conclude this article by arguing that it was merely political separatism which drew the two communities apart. North India’s culture, even to this day, is predominantly Muslim.