At nearly 67 years, Pakistan is a relatively new country. However, its recent history has exhibited considerable structural, political, ethnic and religious conflicts, which keep the country in an underdeveloped state.

In trying to understand its multiple predicaments, scholars have mostly focused on either its recent past or on the ‘Pakistan Movement’ era, thereby leaving large swathes of history barely studied. Therefore, in mid April 2014, the Department of History, Forman Christian College, in conjunction with the Higher Education Commission and the Fulbright programme, hosted a conference entitled ‘Pakistan: Creation and Consolidation.’

The idea behind the conference was two-fold. First, the conference hoped to bridge the 1947 line. While the Partition and independence of India and Pakistan in 1947 was indeed a watershed moment, history did not end or begin from there. Therefore, the conference aimed to situate Pakistan in a broader, more encompassing, timeframe. Second, the conference wanted to focus on the first decade of Pakistan as its formative phase.

In a country’s consolidation, the first decade or so remains a defining period; the same was true for Pakistan. Almost all of the current problems of Pakistan: Islamisation, ascendancy of the military, weak democratic institutions, provincial disharmony, etc. trace themselves to the first decade after independence. However, there are relatively few books on the period. A number of books do indeed start from the first decade, but then quickly move on to other issues. Only a handful of books have ever analysed issues from the first decade alone and how they set a certain trajectory for Pakistan.

Hence there is a great dearth of research on the first decade of Pakistan, and unless we understand and assess this critical period in the history of Pakistan we will be unable to understand its present. This conference was a small attempt to rectify this failing with a hope that the conference would spur on further research on the subject.

The conference began with a superb keynote address by Professor Ayesha Jalal in which she discussed important themes from the first decade of Pakistan and set the tone for the rest of the six panels. Prof Jalal argued that the choices Pakistan made during the first decade still resonate today and need to be further researched and assessed. Lamenting the state of archives in the country, the author of the path breaking, The State of Martial Rule, said that "access to historical documents remains the biggest hurdle" for academic research in Pakistan.

Without access to archives -- and she noted that at times important material was simply burnt -- one cannot write analytical history. Hence the trend in Pakistan has been to write boring narratives with scanty information and eulogies of rulers, often patronised by the rulers themselves. This trend needs to be reversed if Pakistan is to come to terms with its history and move on, Prof Jalal argued.

The first panel of the conference focused on the impact, memory and legacy of Partition in Pakistan. Bringing in insights from her recent interviews, Dr Pippa Virdee, talked about how the Partition still remains a defining memory in the minds of the people in both Pakistani and Indian Punjab, and explored how it affected the nation building processes in both countries. She also noted that despite strict visa regimes, the similarities of language, dress and food still remain between the two sides of the Punjab, aspects which further problematise the consideration of 1947 a firm dividing line.

Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed then further focused on the "Partition syndrome" making important connections between the happenings of Partition and the ‘predicaments of the Pakistani state-building and nation-building projects." Addressing the creation of Pakistan from another perspective, Professor Vazira Zamindar analysed Dr Ambedkar’s text, ‘Pakistan or the Partition of India,’ as the ‘very social history of Partition itself.’

Focusing on nation, displacement and violence, Professor Zamindar situated Dr Ambedkar’s text in the broader context of postcolonial nationhood. Taken together, this panel built upon the flourishing research on the Partition of India and underscored its seminal and continuing defining role in the construction of nationhood in both Pakistan and India.

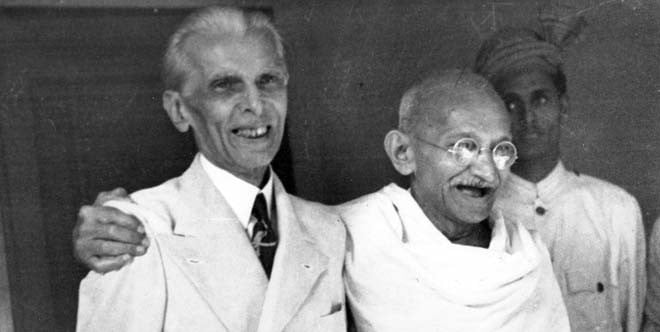

The second panel focused on the role of Jinnah. While no one questions Jinnah’s role as the ‘sole spokesman’ -- as Ayesha Jalal puts it, in the creation of Pakistan, his legacy is still very much contested. What kind of a state did Jinnah want? What were his aspirations for Pakistan? What space did he envisage for the minorities in the new state? -- answers to these questions are still contested. Therefore, this panel brought together three scholars to discuss Jinnah’s legacy.

Speaking on the topic, Professor Sharif al Mujahid argued that by the end of 1946, the statesman in Jinnah overtook Jinnah the politician. Professor Mujahid said that ‘this shift enabled him to fathom and articulate the dictates of the new ground realities and envision a viable future on their basis, leading him to proclaim the Two-Nation States paradigm in place of his Two-Nation Theory.’ He maintained that Jinnah wanted an ‘indivisible Pakistani nationhood.’ Therefore, Professor Mujahid claimed that Jinnah did not want any distinctions between the citizens of Pakistan on the basis of religion or caste, and saw the establishment of the two sovereign countries of India and Pakistan now containing two separate nations.

Agreeing with Professor Mujahid and commenting on Jinnah’s attitude towards the minorities, Dr Farooq Dar exclaimed that Jinnah indeed wanted all minorities to become full members of the newly-established nation. Dr Dar quoted various speeches of Jinnah pre and post-independence to underscore that Jinnah wanted all the minorities to have full rights and contribute to the development of the country.

Extending the argument of his seminal work, Dr Sikandar Hayat then, argued how Jinnah’s charisma -- critical in ensuring the total following of the Muslims of India during the Pakistan Movement -- was ‘routinised’ in the state of Pakistan. This factor gave the state of Pakistan a certain level of stability at a time when the state was under intense internal and external pressures. This panel showed that while Jinnah’s speeches in support of minority rights are not contested, their realisation within the context of a state established for the Muslim community of India remains problematic.

During the discussion on Jinnah later, Prof. Ayesha Jalal made an intervention and exclaimed that why were we still talking about ‘Jinnah’s Pakistan’ while Jinnah himself said several times that Pakistan would be what its people want it to be. "So the work is ours, not Jinnah’s", Professor Jalal argued.

The third panel focused on issues relating to identity and ideology. In this panel, Professor Pervez Hoodbhoy revisited the old issue of Pakistan as either a ‘Muslim’ or ‘Islamic’ state. He argued that defining the nature of polity in Pakistan in this context is really essential to settle the future trajectory of Pakistan. Then in his talk, Professor Iftikhar Malik analysed Pakistan from the perspective of a ‘Modernist Muslim Utopia.’

Tracing the intellectual history of the ideas which led to the creation of Pakistan, Professor Malik situated the creation of Pakistan within the context of the pan-Indian and pan-Islamic modernist discourse. He highlighted that the ‘debate among Indian Muslims spread over an extended time that looked similar to what we witnessed in contemporary Egypt, Russia, the Balkans and Turkey and which got assiduously solidified by the Japanese victory over Russia in 1905,’ as the intellectual tradition which led to the creation of Pakistan.

Speaking on the issue of ‘Language, Modernity and Identity,’ Professor Tariq Rahman, who has recently been awarded the Doctor of Letters degree by the University of Sheffield, argued that one of the primary complications of Pakistan is the primacy of religious identity over the nationalist (political) identity. He stated that "the state’s use of Islamic symbols and discourses, again in the perceived interest of some major decision-makers like Ziaul Haq, had increased the number of sectarian identities and increase the salience of the religious identity which may be a source of increased conflict in Pakistan."

Giving more credence to Professor Rahman’s argument, Dr Mubarak Ali in his talk traced the way in which the Islamic identity of Pakistan was formulated post-independence in primarily religious terms. The overemphasis on religion meant, Dr Ali argued, that Pakistan lost touch with its non-Islamic history, and even began to disassociate itself from the geographical realities -- i.e., South Asia -- and began to look towards the Middle East or Central Asia as its natural geographical context. The urge to be ’ from India also led to the development of this polarised and exclusive identity, Dr Mubarak Ali maintained.

The one question which kept resonating with the speakers -- and the participants, I suspect -- was that which ‘kind’ of a country was/is Pakistan supposed to be? Should Pakistanis still debate what Jinnah wanted it to be and follow that path, or, as Professor Jalal pointed out above, take the matter in our own hands and decide for ourselves what kind of a country we want it to be?

From the panel it was clear that the contestation over Pakistan’s ‘identify’ and later ‘ideology’ polarised the country, and even led to its vivisection in 1971, but that it yet remains an unresolved issue. While most countries do not have a clear cut ‘identity’ or ‘ideology’ they do still have a broad agreement on what constitutes the essential elements of its polity. This broad consensus gives the country a certain degree of depth, stability and direction.

With such a critical factor so deeply contested from the inception of the country, Pakistan’s problems today are not surprising or new. This panel clearly showed that the creation of a broad-based consensus rooted in what the people of the country actually want is the sine qua non for the future development of the country.

Part II of this article will discuss the next three panels of the conference and their implications.