One could presume that books were invented by married individuals so that they have a good excuse to enjoy their privacy. But while they are involved in a book, a vast world unfolds before them; it becomes the key to many secrets locations and longings.

One is bound to be disappointed to find a book without any letters and text; even though each book is in a way blank because it is the reader who completes it by interpreting it and making it relevant for himself. Actually a book cannot survive without a reader. For instance a book in Hebrew would be a useless object in a society that speaks Korean. Thus it is the reader who deciphers the language and transforms it into meaningful ideas. Rarely is a book liberated from the confines of a certain language and understood as a critique on language.

In Amna Ilyas’s new work, this aspect of language is explored. Majority of her work is made up of words or constructed in the form of books. Yet these books do not fall under the category of normal paper-bound volumes. Instead the artist has investigated the format of this product as a formal quest that has led to conceptual excursions.

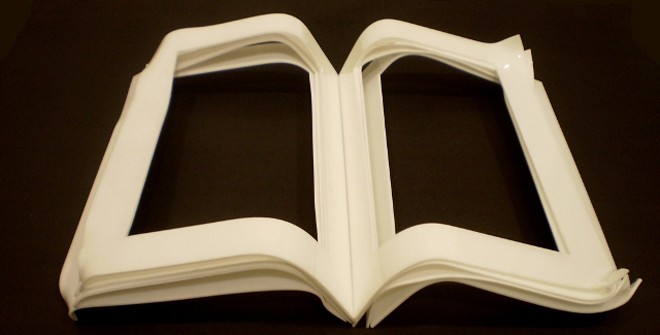

Amid her solo exhibition at the Canvas Gallery Karachi (April 22-May 1, 2014), the artist has constructed books in a range of materials which appear close to paper but are drastically different from our usual experience with paper. In a number of works, books are created in transparent or opaque plastics which seem to substitute the whiteness of the paper. In these open books, one comes across pages on both sides, with either words etched on to the surface or straight lines or just hollow spaces.

Due to the immaculate fabrication of her work -- to the extent that pages are spread like an actual book, or sheets are turned from their corners, like an actual paper exposed to heat and sun -- a viewer tends to believe in the reality of these volumes. At the same time, one is aware of how the whole process of knowledge is part of a large act of power that creates an illusion of truth that is ephemeral and transitory but does not match with the truth.

Thus in her solo exhibition, plastic books appear too convincing but as soon as you try to leaf through one volume you realise the lack of that possibility, since the so-called pages are placed on top of each other and reveal their meagre merger and compromised compositions while touching. The interesting aspect of her work is the distance between real and imagined. It convinces a viewer about the reality of the book but the structure of the work defies the truth about the text. Instead, it challenges all the norms, dogmas, information and accepted version of facts.

The hollow space inside an open book can not communicate except the verbal noise (which surrounds us) that is no more than an exercise in rhetoric. These carved out books describe how our culture is more attuned to the tone of a text rather than its actual formulation. Like the rhythm of mathematical tables memorised by children at government schools, the public has grown on hearing proclamations about national pride, patriotism, glorious past and supremacy of local culture through talk shows, newspaper articles and public speeches. In addition to books, Amna Ilyas has made a number of crumpled pages on top of each other in plastic. The accuracy in fabrication and the sophistication in execution make these works remarkable and extend the artist’s concept of language being a tool as well as a taboo. The textured papers fabricated in plastic on top of each other or placed next to each other and overlapped on a wall depict a sense of sacred as well as profane, because if a sacred text is revered due to its historical significance, a secular document is admired because of its effect on a large community. The experience of these papers, which do not mean anything but seem significant, reveals the status of our state in which grave matters are attempted to be solved on a primary level.

The power and play of langue does not stop here because, in a number of other works, Ilyas questions the position of text as an image; for instance a work in which the word ‘image’ is repeated and layered many times. Here the contradiction between the text being a meaningful entity or just a visual substance is invoked, a question that must have engaged the practitioners of Islamic calligraphy who were dealing with the difference between the content of sacred script and the art of transcribing beautiful forms.

In Ilyas’s works too, the distance between a readable text and a pictorially-pleasing image is fast creeping up, soon to disappear. The culmination of this quest and search of verbal expression and visual exploration is manifested in a body of works in which letters of alphabets, either in black or red, are superimposed on top of each other or occupy the surfaces of mirror-like materials. Here the artist is commenting upon the limitation of the language in comparison to visual expression; yet the work is an amalgamation of the both.

In Amna Ilyas’s work, even though it is all concocted with words, one detects a limitation of verbal expression which the artist has tried to surpass and conquer by transforming words and images. But the battle between the two still continues, even in the practice of art criticism.