Lahore is currently witnessing a revival of serious Punjabi theatre. The most recent Punjabi production to be staged at the Alhamra The Mall is Rahu--The Play, produced by Shah Fahad (of Dramaducation) and directed by Faheem Muzaffar.

It is a theatrical adaptation of the 1950s’ Japanese movie, titled ‘Roshomon, which was based on the Japanese short story, ‘In a Grove,’ written by Ryunosuke Akutagawa. Directed by the award-winning Akira Kurosawa, the movie had brought Japanese cinema to the attention of the Western audiences. The period drama’s deep impact on media had even led to the birth of the phrase ‘the Roshomon effect,’ a reference to multiple contradictory interpretations of the same event that make it difficult to ascertain the truth.

Obscurity of truth is at the heart of Rahu--The Play. The title is an allusion to the Hindu mythological figure of Rahu, a murdered man whose dismembered head is said to have attained immortality. According to Hindu mythical and astrological beliefs, a solar eclipse occurs whenever Rahu’s head devours the sun.

The director utilises Akira’s techniques to portray the lack of figurative and literal light in a story that is trying to decide which one of the multiple narratives is based on truth.

The plot revolves around the twin incidents of murder and rape that occurred in a forest over 1,500 years ago. While the crime is certain, the problem lies in uncovering the identity of the real culprit. The bandit accused of the heinous crimes, Jago Singh Surma; Mutiyar, the raped wife of Sardar Kasar; and the ghost of Ameer Kasar, the murdered Swami belonging to the ruling family, all relate contradictory versions of the event.

The story unfolds through the conversation a perplexed Jogi has with a common carpenter, Tarkhan, who first discovered the dead body. Their rehashing of the three characters’ court testimonies is interrupted -- and interpreted -- by the appearance of a petty thief who calls himself the "Bazigar".

While the storyline of Rahu is borrowed from Roshomon’s, the stylistic devices used by the director here convert it into a distinctly Punjabi play.

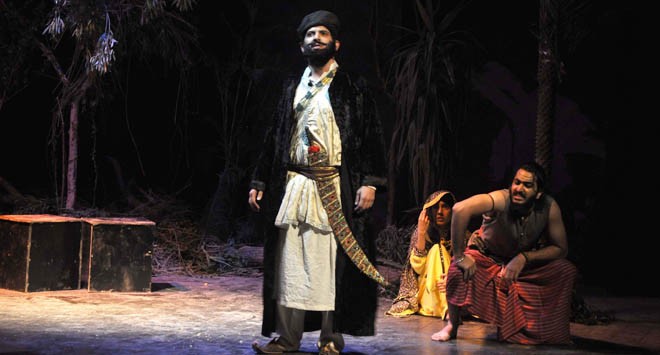

Prior to the commencement of the play, the audience was treated to a live rendition of sufiyana kalam to the accompaniment of harmonium and tabla. The play then began with the cawing of a ‘human-crow’ in a dark and barren place while a jogi meditates in the background.

The utilisation of the cawing crow, a Punjabi symbol for foreboding, sets the scene for a grim tale to come. The disgust of Jogi (played by Usman Zia) at the nature of mankind and his reverent disciple Tarkhan (Afnan Dogar) attempts to pacify him unfold in a rundown ruin symbolically shrouded in darkness.

The thunderstorm that forces these two to put up with the foul-mouthed Bazigar (Shah Fahad) gradually gives way to clearer skies as the story progresses towards the end.

Even though the play uses Akira’s ploy of telling a story through flashbacks and flashbacks-within-flashbacks, the typically Punjabi tradition of oral-storytelling through songs is highlighted by the buffoonery of the irreverent Bazigar.

Also differentiating the play from its Japanese inspiration is the stylistic technique of elevating the audience to the status of the judge. Addressed, with varying levels of respect by different characters, as "Huzoor," the theatrical ploy very cleverly makes the audience a part of the play while letting them reach their own conclusions about a story with no clear resolution.

In keeping with the time period in which Rahu is set, the characters are afforded respect and dignity according to their status in an ancient Punjabi society. This is apparent through the deliberate refusal to name the only woman’s character. Though she is one of the central characters of the play, she is throughout referred to as ‘zanani’ or ‘mutiyar’ (Aimen Shahid).

Similarly, she is identified through the course of the story either as her husband’s wife or father’s daughter. Adding to this stereotypical view of women is the perception of all women as the root cause of all evil. Whether that is true or not, is left for the viewers to decide.

Other characters who reside on the lower rungs of social hierarchy, such as the tarkhan and the sipahi, are also treated with the same lack of name (or respect, if you like). Interestingly, the character considered having the least amount of morality and finesse by the rest of the characters, Bazigar, seems to be the wisest of them all. In this instance, the director and the scriptwriter of Rahu appear to have been inspired by the buffoon/Fool in Shakespearean plays.

This leads to the central theme of ‘appearance vs reality’ in a play where nothing is as it seems. All the accounts about the crime are tinged with the characters’ inherent selfish and egotistical motives. It is difficult to decide whether Jogi is the real seer in the play. Tarkhan and Bazigar are equally wise and, in fact, more in tune with the grim realities of human nature.

The play ends on a note of hope embodied in the presence of the abandoned baby whose existence provides humanity with another chance to redeem itself.

It is commendable that the cast and the crew of the Punjabi production were able to portray the complexity of their story without a major flaw. The minimalist set added to the harsh tale supported by a brilliant cast. All three of the central characters, namely Jagoo, Mutiyar and Jogi, could be viewed as protagonists on the strength of their acting skills alone.

The beautifully choreographed duels between Jagoo and Ameer lent an age-old Punjabi feel to the story while staying true to the Japanese roots of the plot.

It is hoped that an extremely well put together theatrical production like Rahu--The Play shall help to attract more serious actors and viewers to Punjabi theatre.