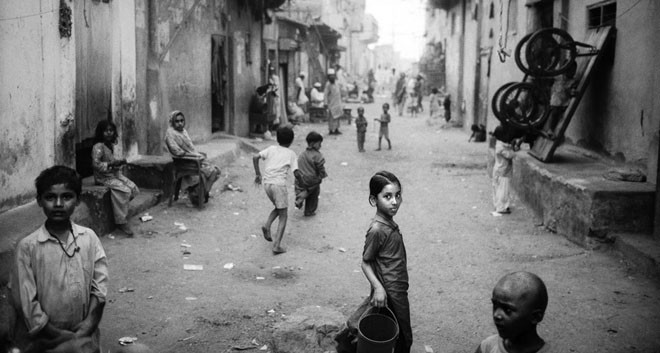

An open drain cuts through the settlement and streams its sewerage into the sea; polythene bags float at its surface; plastic pipes from nearby houses lead into this dirty water body and there are more houseflies than mosquitoes lurking around… A myriad of smells, of fish and human excrement, greet a first-time visitor to the Machar Colony in Karachi.

This squatter settlement by the Karachi Port is spread over miles of brick huts with tin roofs. Over 300,000 inhabitants live here, mostly of Bengali and Burmese descent, who occupy the lowest rung of the $1.2 billion fishing industry. A number of Kachchis, Mohajir and Pashtun inhabit this area as well.

Its proximity to the violence-ridden Lyari sometimes creates a spillover of gang wars, when law enforcers cordon off the area to conduct search operations, rummaging through each house in search of refuge-seeking gangsters. Often, police pick up young boys on mere suspicion.

A day at the settlement begins with a visit to the vara, a place where fishing trawlers dump shrimps and small fish and where women and children queue up as early as five in the morning to grab as many baskets filled with shrimp and fish as possible. They return home with their baskets and peel it all day. Each basket earns them Rs20. On a good day, a family may earn up to Rs100.

Child labour is rampant in the Colony because nibble fingers do the job best. "Sometimes fish bones get stuck in my fingers. The ice in the basket make my fingers go numb. To soothe the pain, I apply henna on my fingers," says nine-year-old Sanjeeda.

Fishing or fishing-related jobs are common -- some men in groups of 70 or 80 go on long fishing trips to the sea, others work in fish packaging factories.

The port also employs men as labour force from the Machar Colony.

The Urban Resource Centre, a think-tank that focuses on civic issue of the city, states this is the oldest settlement in Karachi. In fact, this is where the city started to spread from when fishermen in small groups began to settle by the port.

The land belongs to the Karachi Port Trust. In past, attempts to evict the area have been resisted by resident, who look at the KPT as outsiders, out to grab houses they claim they own.

"I bought this house in installments. I even have documents to prove it," says Jaffar Babu, an elderly man who lives in the area.

As a general practice, land grabbers look for an empty piece of land, demarcate plots and sell them to the poor on installments. The working-class families pounce on the opportunity to own their own house near their place of work in big city Karachi.

In 2009, a resolution was passed in the Sindh Assembly where 39 squatter settlements of Karachi were made legal. Machar Colony was in the list. But later the KPT claimed that the Colony was their land and they worked under the federal government.

The area was once a stronghold of the Pakistan Peoples Party. However, in the 2013 elections, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement bagged the seat for the National Assembly while the provincial seat went to the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz.

Inside the settlement, it seems the state does not exist. The rights the constitution guarantees its citizens are a distant dream. In the absence of pipelines, drinking water is drawn through privately-owned hand pumps. Each container costs Rs20 to Rs30. "Sometimes sewerage water mixes with drinking water. It makes our children sick," says Amir Bano.

Health and hygiene is a major issue. Families of 10 to 12 people live in a single-room houses, with common toilets. A measles outbreak last year took the lives of several children, claim doctors at a clinic run by Doctors Without Borders, an international NGO.

"Drug addiction among men is common. Complaints of depression, psychosis and aggression are on the rise. Poverty has pushed these people into a general despair with life," says Saniya Amin, a psychologist who works at the clinic.

Till last year, not a single hospital operated in the area. Dais would deliver babies and charge anything between Rs1000 and Rs2000, depending on the sex of the baby born.

About 50 low-cost private schools and a handful of madrassas operate in the settlement. Four schools run by The Citizens Foundation have been providing quality education since 1995.

"I have parents coming in at all odd times of the year for they want to get their children admitted. When I tell them there are no vacant seats in classrooms, they offer to bring their own chairs from home," laughs the principal of a primary school.

Students work and study simultaneously, often getting as little as three hours of sleep at night. "Education is the only way out for us," says 12-year-old student Abdul Shakoor.

When elections are around the corner, politicians make big promises of providing health, education, safe water and respite from crime. But after securing votes they move out and keep busy with more important issues. Resultantly, the unemployed youth of the area join militant gangs run by political parties of the city. They loot and plunder on their command. But when they get caught by law enforcers, they are disposed off.

"We are like tissue paper. Police pick our boys and deny us links to them. They languish in prison," says a resident, Ahmed Akhtar.

An earlier version of the article incorrectly stated that a measles outbreak last year took the lives of 400 children. The error is regretted.