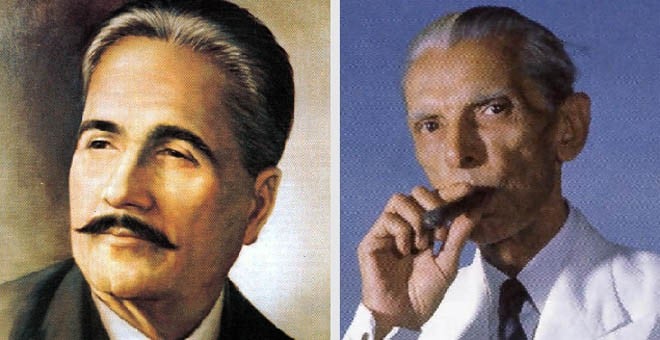

The articles by Yassir Pirzada and Ayaz Amir rattled deeply entrenched stereotypes about Pakistan’s founding fathers, vociferously articulated by "the patriotic brigade" (as described by Ayaz Amir). The principal interlocutors of the patriotic brigade unequivocally adhere to the static narrative which has a linear trajectory and centres on the sanctification of the figures of Allama Iqbal and Quaid-i-Azam.

The Pakistani national discourse is stuck in time. The narrative remains alive and responsive to temporal exigencies only if it deals with human and not mythic figures. The irony, therefore, is that in general perception both personalities are completely divested of any human or mortal attributes. The process of their sanctification has transposed them beyond the realm of humans made of flesh and blood.

Renowned historian and author of an influential work What is History, Edward Hallett Carr (1892-1982), earnestly argues that each generation needs to have its own history written afresh. But, Pakistani history seems to have been etched in stone, characterised by the symbolic appropriation of figures to consolidate and strengthen the ideological ends of the patriotic brigade. Indeed, this only works where figures are first de-contextualised from their position as historical actors, and then reconstructed as mythical figures conforming to a particular ideological narrative. That ideological narrative, steeped in religion, espoused by the detractors of the two columnists, has now been appropriated by the TTP, leaving us at an intellectual crossroads with a choice to make.

And, if that ideological narrative is allowed to run its course, then the state of Pakistan will be in jeopardy, if not already in such a state.

Now is the time for another narrative -- privileging the state over ideology. To do that, we will have to take Carr’s advice seriously.

Thus, the sanctification of the founding fathers and construction of a discourse around it is the primary reason why any revision in Pakistani history does not seem imminent. Importantly enough, the ‘scholars of sorts’, who constitute that brigade, wielded their pens to refute the points of view expressed by Pirzada and Amir. They are in fact rather exclusivist when it comes to reading of historical events.

The classical tradition of hagiography has permeated deep into our cognitive culture, which had a pervasive rub on the disciplines of History and the allied social sciences. Remorsefully, such morbid trends are then jealously guarded by these ideologues. To them, the critical appreciation of personalities or historical events is a tabooed and preposterous act. One who professes that is demonised as ghaddar, therefore condemnable.

Yassir Pirzada barely escaped absolute condemnation because of his grandfather, Maulana Bahaul Haq Qasmi and the services that he putatively rendered for the cause of Islam. Pirzada was not branded ‘secular’ or a ‘liberal fascist’ since he enjoys the luxury of having forebears who were on the ‘right’ side of the fence. Anyone with ‘right’ credentials has far greater chance to pervade through the muddied waters. He was merely chastised, despite his (vain) attempt to vindicate his claim by citing various sources in his column, which generally is a practice not followed by columnists.

The promising thing is that along with Wajahat Masud, Pirzada has added some vitality to the liberal voice, which exists only at the margins in the Urdu media.

Interestingly enough, a re-imagining of Iqbal is far more complete and thorough than Quaid-i-Azam. However, Iqbal’s prominence mostly rests with his poetry simply because his religious/philosophical thought is so radical and denies any role to the clergy, and so it is not talked about much.

Iqbal’s role in active politics is shrouded in ambivalence. Even AshiqueHussainBatalvi’s book Iqbal key Akhari do Saal did not spend as much time on discussing Iqbal’s politics as it did on the politics of Sir Fazl-i-Hussain. Iqbal’s response to the Khilafat Movement was no different than that of Quaid-i-Azam, who saw it with distaste.

Iqbal spent most of his time in intellectual engagement during the major part of 1920s (despite the fact that he was the member of the Punjab Legislative Council from 1927 to 1930 from Unionist Party). He participated in the meetings of Anjuman-i-Himayat-i-Islam, which was more of a cultural rather than a political activity in its essence.

Similarly, one does not see any reference to Jallianwala Bagh incident in Zinda Rood, which is otherwise a remarkable biography of Iqbal. Thus, the response on Ayaz Amir’s statement about Iqbal’s reticence on Jallianwala Bagh incident was absolutely uncalled for. The conclusive argument, therefore, is that such ‘aberrations’, if that is what they were, do not lower the greatness of these historical figures. What is important, however, is that historical figures should be treated as such and not as mythic figures.

Detractors of critical thinking are absolutely impervious to how the academic world outside Pakistan imagines Allama Iqbal and Quaid-i-Azam, and their respective roles in the history and politics. I am really interested to hear the feedback of that overzealous patriotic brigade to Ayaz Amir’s taunt about locally produced biographies being shoddy and substandard.

While not sitting in judgment over the merits of the locally churned out scholarship about Quaid-i-Azam and Iqbal, I will nevertheless underscore the divergence (in Pakistan and the Western academia) in the ways the role of both the ‘historical figures’ is being contextualised and understood. The international perception about them is formed through the works of Ayesha Jalal (regarding Quaid-i-Azam) and JavedMajeed (regarding Iqbal). It is largely because such scholars deal with them critically and not by deifying them.