Having passed out from the university, the intention was firmly to take my father’s advice and find a clean, gentlemanly job that would fetch five hundred to a thousand rupees a month. But times then were just as they are now; a Masters degree from the university could barely get you a lowly clerical position.

So one allowed oneself to be led by one’s instinct.

The result was predictable. Ten rupees that I got as pocket money from home took me through a day at the Karachi Press Club (KPC), which was one place where I could satisfy the political fetish I had contacted from my university days.

The KPC’s president at that time, Abdul Hameed Chhapra, was like a godfather to Karachi’s journalist community. Rookies aspiring to be newsmen could count on him for everything -- from getting them a copyboy’s job to teaching them tricks of the trade, and even offering them a bit of rare evening fun by inviting them over to the KPC bar.

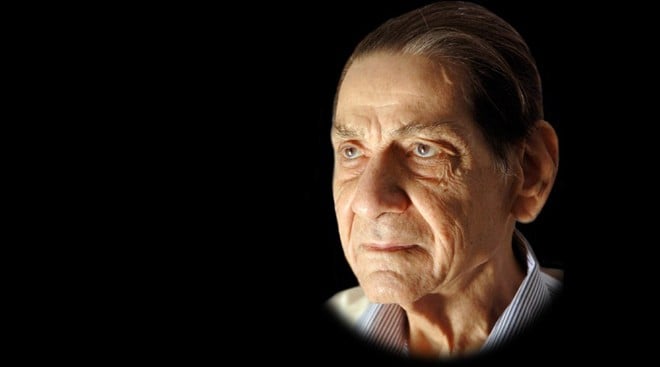

Chhapra Saab was the pivot around which the community turned. It was during those rotations that I got an introduction with Ashraf Shaad, and found a 300-rupee-a-month reporter’s job at the pro-Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) weekly magazine, Mayaar, which was edited by Mehmood Shaam. During my evenings at the KPC, I would often notice local hacks -- known and not-so-known -- trickle in one by one and gather around a middle-aged, fair skinned man with a stout physique and a serious look on his face. Everybody called him Barna Saab.

Those were times when juniors truly stood in awe of their seniors and few could muster the courage to walk up to them and get an introduction. I was to wait until the stormy days of Pakistan’s third military coup to get to know Barna Saab better.

After toppling Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the founder of PPP, the military regime of General Ziaul Haq also slapped a ban on the PPP’s official newspaper, Musawat. Resentment had already been brewing among journalists. The ban sparked public protests, and group after group of journalists started to court arrests. One day, I was also asked to join a group. We spent a couple of months in the jails in Karachi and Hyderabad.

Minhaj Barna was detained in Khairpur jail, and had embarked on a hunger strike. The protest was gathering momentum, and it soon started to draw hundreds of students, industrial workers and peasants to its fold. The regime was forced to change tactics. It agreed to a deal with the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists (PFUJ) that led to the lifting of the ban on Musawat and release of all the arrested activists.

Having been a jailbird turned me into an authentic commodity and earned me a place at the gatherings around Minhaj Barna. These evening get-togethers offered me a chance to know him from close quarters. He was an intelligent man with well-groomed ideas and a great sense of humour. And he was humble -- a novice like me could expect total respect from him. And we could discuss with him anything -- questions regarding who to meet and who to avoid, which political slogans to chant and which ones to discard, and take how much water to soften a hard drink.

The wise men of yore have said that you get to know a person better when you eat at his table. I qualified to Barna Saab’s dining table after I had spent a couple of years doing journalism, had become the joint secretary of KPC and had learned the art of public speaking and arranging public gatherings.

This brought me into contact with Lahore’s prominent journalist, Nisar Osmani, and the Poet of the People, Habib Jalib. It was the company of these great people that marked all our gatherings at Barna Saab’s Gulshan-e-Iqbal residence in Karachi. I have been a part of those gatherings not for months, but years. What I and the likes of me can write or say today is owed to those evenings.

Barna Saab’s wife was from Czechoslovakia. She stood resolutely by his side through long periods of his incarceration or unemployment. Despite that, she was a great host. This was in sharp contrast to many members of our journalists’ community who were otherwise habitual drinkers but at home observed all the rituals of abstentious chastity. I can claim that I wasn’t part of that tribe, and the credit goes entirely to my wife, Nuzhat Shirin, who partly learnt the art of hospitality from Mrs Barna.

She would speak to Nuzhat in broken Urdu, telling her how to look after her guests. "You must always have a dish of lentils, a dish of vegetables, some meat -- and don’t forget shami kabab. And there must be a dessert, and fruits…."

Barna Saab took care of his wife bravely during her last days. It is a painful tale to tell. Barna Saab gave the best years of his life to the protection of journalists’ rights, but the journalist community sang his obituary long before we actually assigned him to dust.

The politics of ideology has a merciless flip side. When it inspires you, it makes you put everything on the line, but when splits take place, the very people who once shared a dream and struggled together to bring it to reality become enemies of each other.

This happened during the USSR versus China fallout among the Pakistani communists during the 1980s, and also affected the PFUJ. Journalist leaders whose words once turned to flowers when they spoke fell to such depths of ignominy that their words and their gestures still shame those who remember them.

During this period of no-holds-barred hostility, Minhaj Barna must be placed at the top of the list of those who retained personal dignity and ideological vision.

The so-called ‘independent media’ of Pakistan neither knows nor wants to know who Minhaj Barna is and how he is relevant to the press freedom in Pakistan. Many underlings who have spent a few years in the mega-circulation newspapers or high-rating television channels believe they have done more than anyone else. You can’t miss them congratulating themselves in newspaper columns and TV talk shows. Few of them know what it means to be without a job, or to suffer indignities at the hands of the police and jail staff, and still retain one’s self-respect.

Most of us who in the 1980s and 1990s were wedded to the slogan, "tere saath jeena, tere saath marna, Minhaj Barna, Minhaj Barna" (we will live with you, we will die with you, O Minhaj Barna), broke down when confronted with the bitter reality. To put it simply, when your children are begging you for food, and the landlord is knocking at the door for rent, I for one must confess that it gives you a powerful urge to stop hanging around the ‘party’ offices and the press club.

I did the same. Let me not go into details of my tough days. Suffice to say that when I first received my pay cheque for shooting my mouth off at a private television channel, I held to it so fast I let go of all my philosophical and ideological baggage.

The advent of the electronic media undermined the print journalism and sent to oblivion the icons of press freedom who had suffered years of confinement and penury, and who died spitting blood. To use the words of Hamid Aziz Madani

Wo jin ke dum se teri bazm mein thai hangamay,

Gaye to kiya teri bazm-e-Khayal se bhi gaye?

(Those, who made your feasty gatherings lively, have they fallen from the gatherings of your thoughts as well?)

Chiragh Hasan Hasrat, Mazhar Ali Khan, Sibt-e-Hasan, Nisar Osmani, Khalid Alig, Hasan Abidi, Paikar Naqvi, Ibrahim Jalis, Zamir Niazi, Minhaj Barna -- how many names and their deeds are remembered by today’s ‘independent’ and ‘popular’ media?