As the peace talks between the government and the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) got underway in early February, attention soon turned to the issue of the persons in the custody of the two sides and there was intense speculation about a possible exchange of prisoners and release of the non-combatants in the first phase.

It is an emotional issue and could even make or break the fledgling peace process.

Sentiments could easily flare up on the issue as it happened when the TTP’s Mohmand Agency commander Omar Khalid Khorasani, a hardliner in an organisation known for its radical and violent approach, announced that 23 Frontier Corps soldiers in his custody for more than three-and-a-half years had been executed to avenge the death of militants held by the government. As he has neither returned the bodies nor identified their graves, the issue has caused much pain and stiffened the attitude of the military towards the militants.

The killings apparently took place in Afghanistan, where the TTP militants found refuge in Kunar, Nangarhar and Nuristan provinces after suffering defeat at the hands of Pakistan’s security forces in Swat district and Mohmand and Bajaur tribal agencies in 2009.

The execution of prisoners was a major provocation on the part of the militants and couldn’t be ignored. As a mark of protest, the government negotiators decided to discontinue the peace talks. The process was resumed when the TTP agreed to a unilateral and unconditional ceasefire on March 1 and subsequently the first round of direct peace talks between the two sides was held in Taliban-controlled area of Bilandkhel in Orakzai Agency.

Now that the government has started releasing prisoners suspected of having links to the TTP or those cleared by the security authorities, there is growing expectation that the militants too would positively respond to the gesture and agree to set free civilians in their custody. These men, and also a few Western women, were kidnapped for ransom and for securing the release of militants held by the government, mostly by the security forces.

The two Czech women kidnapped are Hana Humpalova and Antonie Carastecka who were seized by unidentified gunmen in Balochistan province in March 2013 and reportedly taken to Waziristan. Two video-tapes of these girls have been issued in which they are begging for their release in return for acceptance of the militants’ demands. More poignant was the video recorded by their mothers in which they are appealing for mercy and freedom for the two young women.

Other kidnapped Westerners include Warren Weinstein, an American consultant seized in Lahore in September 2010 and reportedly in custody of an al-Qaeda-linked militant group and German aid worker Bernd Muhlenbeck and his Italian colleague Giovanni Lo Porto, both taken away by Taliban militants from Multan in January 2012 while doing humanitarian work for the affectees of the 2010 floods.

Beverly Giesbrecht, a Canadian blogger in her late fifties who became Khadija Abdul Qahar after claiming to have converted to Islam, died in the custody of the kidnappers in November 2010 in North Waziristan after being seized by the militants in Frontier Region Bannu in November 2008. Her kidnappers had demanded release of Dr Aafia Siddiqui by the US government and some militants held by Pakistan’s military and $2 million as ransom.

Some of the kidnapped men were lucky to be released, though a huge price had to be paid in the process. Amir Malik, a wealthy jeweller kidnapped from Lahore in August 2010 is the son-in-law of General (Retd) Tariq Majeed, who at the time was serving as chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee. He was subsequently freed but the details of the deal that secured his release are a matter of speculation. Dr Lutfullah Kakakhel, who was vice-chancellor of Kohat University of Science and Technology when he was kidnapped some years ago, was also fortunate to become a free man again.

Another vice-chancellor, Professor Ajmal Khan, headed the Islamia College University when he was kidnapped in Peshawar on September 7, 2010 and is still in the custody of the militants. The TTP demanded a huge amount as ransom and release of three militants in return for his freedom. The TTP was hoping the previous ANP-led provincial government would accept all its demands for his release because he happened to be ANP head Asfandyar Wali Khan’s cousin, but no deal could be made despite hectic efforts.

Prof Ajmal Khan has the best chances of getting freed as the TTP has admitted holding him and treated him relatively well. However, it may not let him go without forcing the government to accept its demands for release of a militant, Hammad, stated to be one of the kidnappers, and also some of its ‘non-combatant’ prisoners.

The fate of two other high-profile prisoners, former Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani’s son Ali Haider Gilani and late Punjab Governor Salmaan Taseer’s son Shahbaz Taseer, remains uncertain. The TTP is insisting that they weren’t in its custody. However, the government would want the TTP to persuade or force the foreign militants holding them to free them in case the peace talks moved forward or a deal is clinched eventually.

There have been reports that the younger Gilani is in custody of an al-Qaeda-linked group operating in both South Waziristan and North Waziristan. Intriguingly, the kidnappers had for a long time refrained from conveying their demands.

The case of Shahbaz Taseer, kidnapped from Lahore on August 26, 2011, is even more complex as foreign militants affiliated to the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) were holding him somewhere in North Waziristan. The Uzbeks had at one stage demanded the release of 25 prisoners, all Pakistanis except eight Afghans, who were in the custody of the security forces and Rs4 billion as ransom.

Ironically, top of the list was Mumtaz Qadri, the security guard who gunned down Salmaan Taseer in Islamabad on January 4, 2010. The man who was supposed to protect Salmaan Taseer shot him dead because he disagreed with Taseer’s vocal opposition to the country’s blasphemy law. Taseer had earlier met Aasia Bibi, the Christian woman convicted by a court for blasphemy, to show solidarity with her.

Of the eight Afghan militants in the list, at least three have already been released. They are Mulla Mansoor Dadullah, younger brother of late Afghan Taliban commander Mulla Dadullah, Abdul Majid son of Qari Mujib nabbed in Quetta, and Ahmad son of Hakimullah. Mansoor Dadullah, who replaced his brother as a Taliban commander in southwestern Afghanistan before falling out with the Afghan Taliban leadership, was recently freed by the Pakistan government along with more than 40 other Afghan militants on the request of President Hamid Karzai to facilitate peace talks between the Afghan government and Mulla Omar-led Taliban movement.

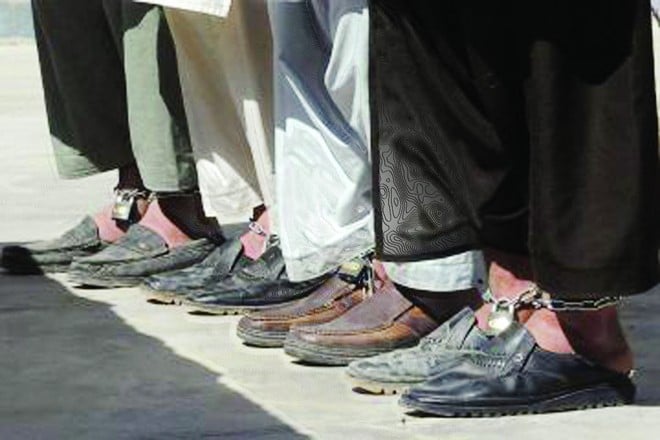

The other, largely unknown men in the militants’ custody include the unaccounted for Frontier Corps soldiers, some low-ranking government employees and coalmine workers. A number of Wapda and Fata mining department employees were freed some weeks ago after payment of ransom.

The militant groups have used kidnappings to secure the release of their men and demand ransom. The Baitullah Mehsud-led TTP in August 2007 was able to obtain the release of a significant number of local and Afghan Taliban militants in return for the freedom of more than 270 Pakistan Army soldiers captured by his men. It is thus obvious that the TTP won’t easily give up even the civilians in custody of the militant factions operating under its command. At the same time, it would continue seeking the release of its men, who in TTP’s opinion are ‘non-combatants’ and were wrongly held despite the fact that there are only two women in the list and no mention of children after all the propaganda by its spokesmen.

It also disowned the 19 Mehsud tribesmen recently released by the security forces in South Waziristan by arguing that they weren’t in the two lists of 800 ‘non-combatant’ prisoners that it gave to the government negotiations team for securing their freedom. The government has promised to free another batch of 13 Taliban prisoners listed by the TTP, but it remains to be seen if they are owned by the outlawed militant group.

With the extended 40-day ceasefire declared by the TTP ending on April 10, there is growing concern in government circles that the militants would increase pressure to seek more releases of their men and use the issue as a bargaining chip.