Not too long ago in these very pages I had commented on the way a writer had handled violence, women, love and desire in his short fiction, particularly the title story, which seemed to have celebrated, even condoned the violent rite of passage the male protagonist must tread before achieving sexual bliss.

Perhaps, I was unfairly harsh. Perhaps, I misread the irony.

But in the following space, I offer a brief analysis of two pointed, effective short stories by two very different writers who handle situations involving murder and women, from male and female perspectives respectively.

Softer by Paolo Bacigalupi is about a man who unwittingly kills his wife by suffocating her with a pillow. The story opens with both the husband and his dead wife, floating, in their bathtub as he considers turning himself in and contemplates the nature of his crime, while sipping wine.

"He’d read somewhere that pot growers got more prison time than murderers… Was it manslaughter? Murder in the second degree? He stirred soap suds, considering. He’d have to Google it." The story opens with this information, then rakes through the moral fibre of the protagonist.

The woman’s murder is not just a backdrop. Bacigalupi introduces the horror of being suffocated to death early on, so as the story nears climax, oscillating between humour and mild sarcasm, the images of a wife struggling to stay alive haunt the reader and lend the humour a tragic tinge.

It all started with her casual remark about him having forgotten to do the dishes and a little nudge with her elbow and "then he jammed the pillow over her face and her hands had come up and gently pushed against him… He meant to take the pillow off her face … But then Pia started struggling and screaming… He couldn’t stand to see the hurt and horror in her gray eyes… so he threw all his weight onto her struggling body… She twisted and flailed. Her nails slashed his cheek. Her body bucked… he buried her screams in the pillow… Her hands whipped… an animal’s panicked thoughtless movements… Her hands… pale butterflies trying to discover the cause of their owner’s distress."

As the story moves on, the reader witnesses the murderer’s progress from moral ambivalence to selfishness while acknowledging his humanity. While the author shows extreme skill to avoid creating a cardboard evil character, what is important is to realise that the writer does not condone violence against a nudging (read: nagging) wife. While centuries of violence against women has conditioned men to assume it less than a crime, they cannot "stand to see the hurt and horror" in their eyes where they see their sins reflected.

Softer thus examines the institution of violence against women as a two-stage phenomenon: playfulness of violence and inability to recognise the horror of it.

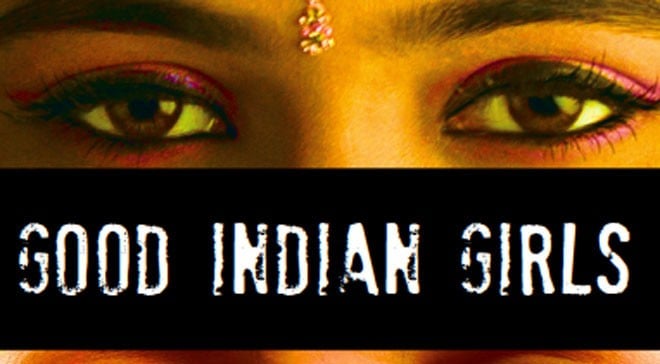

The other story Good Indian Girls by Ranbir Sidhu is more nuanced and ends where Softer begins. It too peeks into the world of horror and violence against women but from the recipient’s end. And it adds an additional layer of a first generation immigrant experience.

The tone of the story is dead serious, and what little humour one detects, turns out to be acerbic such as when the female protagonist Lovedeep joins a de-cluttering class to gain self-confidence, find a better job, and fall in love -- "Lovedeep assumed he was equally irritated by the instructor’s new age quakery".

"The instructor’s an idiot," she reveals to her future-assassin her extreme repulsion at the blonde-haired instructor who confides, "My heart is Indian."

The future assassin’s comments about the inconsequentiality of India and Indian deaths have a colonialist ring and ironically stand in stark contrast to the modern day West’s orientalist obsession with Bollywood song-and-dance, spirituality, and irresistible attraction to poverty porn exemplified by Slumdog Millionaire.

This is not the place to go deep into some of Ranbir Sidhu’s primary concerns. In this story, he also dissects "self-sabotaging behavior" and from this emerges the title of the story. As the story moves on with clinical precision, avoiding verbosity and ribaldry, it combines two themes which compliment each other: senseless violence against women and societal insistence on good girl behaviour. The male ego is synonymous with lack of love.

Dostoevsky has said in The Brothers Karamazov, that I am paraphrasing here, that good and evil have been fighting each other and human heart is the battlefield. Even if we admit, as we should, that there is evil out there bound to find us without us ever having invited it (think of US invasion of places like Iraq or Vietnam), like in the story Appointment in Samara, it matters how we educate and prepare our daughters to resist and stand up to evil.

The man Lovedeep has befriended at the de-cluttering class none other than the infamous Internet Stalker, with the hope of finding love. She learns that after he’s been invited into her apartment. And when puzzled by the situation, she asks him if he hates her. "’Yes,’ he said, ‘I do.’ He added, softly, ‘Don’t take it personally, it’s women."’ There were times when she could have been quick to sense the danger and act, but she had been trained to be good, which her executioner appreciates. "You’ve been the best… You parents raised you well. It’s a shame." Her only consolation is that he is a very gentle man.

A contradiction is automatically embedded in the institution of the benevolent master. This is a razor sharp sentence and not even for a second the reader believes that the author appreciates the protagonist’s view about her executioner, nor he condones the act of violence. It is one thing to make the reader see what violence is and how it operates. It is another to lose one’s own moral clarity to the narrative’s colourful world of violence. Violence may be entertainment to the unrefined mind, it is also the absence of love. And the lines between entertainment and violence can quickly blur. A good writer must resist that temptation.