Life is nothing but a process of decay decorating itself with illusions -- Giuseppe Ungaretti

The Italian poet describes a phenomenon that has reached its zenith in present times. We are facing a continuous cycle of decay; not only in terms of concepts, conventions and customs but also in terms of physical objects deteriorating at an unprecedented speed.

Gone are the days when people used to buy gadgets for life. However, with the rise of consumerism, now industrial items are manufactured in a way that these become defunct in a few years time. It is easier to throw them than getting them repaired.

One wonders about the heaps of abandoned mobile phones, computer monitors, CD players, television screens and such objects of desire and disuse lying in our homes. What will happen to these accumulated piles and piles of plastic, wires and metal? A visit to a junkyard is enough to know how the production industry operates and leaves a huge amount of rubbish.

Today, industrial refuse is an immense issue and has introduced the need of recycling, reuse and finding other consumer communities, preferably beyond the main area of manufacture and merchandising. Thus we have been exposed to an influx of discarded books, DVDs, machinery, clothes and other accessories sent here, and sold in our shops and roadsides.

This procedure of discarding, accumulating and recycling is not limited to physical products; it extends to the realm of ideas as well. This reality of the contemporary world is addressed by artists from various backgrounds, most of them critiquing the spread of consumerism and the altered mode of existence in its aftermath. In Ali Raza’s recent exhibition (Feb 20-March 20, 2014 at Rohtas 2, Lahore), one discerns the artist’s comment on the structure of a society that is exposed to the world of market and products.

Raza has picked a format which, till a few years ago, was favoured for advertisements but with the new developments in technology is not sighted as often. In this format, along with usual posters, a sort of moving billboard was introduced in the field of marketing. Constructed with triangular units, these hoardings had three images which became complete and comprehensible whenever one side was turned frontal and flat with the help of motorised system. For our urban public, the novelty soon wore off with the installation of digital sequences of advertisements. Yet, due to their formal characteristic, the triangular publicity boards hold a special place in our collective memory.

In an environment of truth and deceit, they kind of represent a certain societal trait -- multiple levels of reality. In a single object, one sees three separate sides of the same message; an element that has been a part of advertisement but can be extended to the world fabricated around us, in which academia, media, politicians and religious leaders collaborate in presenting their desired version of facts.

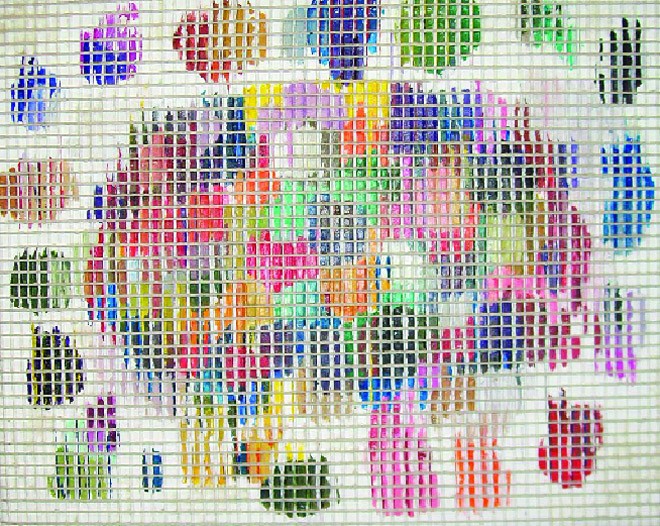

Ali Raza chooses to comment on this phenomenon by painting on similar kinds of construction in his solo exhibition (Seen from Here, There and Nowhere) where one painting is not a single image, but a combination of two or three visuals. Once a viewer moves, he sees a different image from another direction. The selection of this format is not a casual preference because in many works Raza paints burgers, female faces and scenes of beautiful sunsets and waves of sea -- the stock imagery representing an ideal world. It is not limited to glamorous and consumer network of edible and pretty products; he has included pictures from our local media and national heritage. Face of a child and the portrait of Quaid-e-Azam appear different (but not disjointed) from three sides, perhaps alluding to how single characters, incidents and events are transformed due to spectators’ (physical or psychological) position.

More than an optical effect, it also indicates the way history, reality and facts are modified and mutilated on the basis of users’ needs and points of perception.

With his skill in painting, the works communicate the artist’s views on history, culture and art (one can detect references of his contemporaries such as Zahoor ul Akhlaq and Rashid Rana), yet the scale of these pieces do not justify the impact of his content. The decision of reducing triangular hoardings into small surfaces within a gallery can be a formal exercise but due to its size it deflates the ideas of representing reality through grand illusions.

On the other hand, it can be seen as an artist attempting to bring the actual world inside a gallery space and converting a commercial device into an art commodity. This scale is also way of affirming how artists in our part of the world have no experience and exposure to actual dimensions of art from history, but are more familiar with the small scale reproductions of huge works (such as Michelangelo at Sistine Chapel in Rome) in the form of tiny glossy pictures printed in art books. Perhaps, in an unconscious manner, Raza also reduces his adopted imagery, an act that turns these as copies of the copies (reminding one of Plato’s cave as well as the Marx dictum about second version being farce!).

Looking at the work of Ali Raza from his solo exhibition, one realises that size is not just a matter of measurement, it can be an instrument of content too.