"I was walking along a path overgrown with grass, when suddenly I heard from someone

behind, ‘See if you know me?’

I turned round and looked at her and said, ‘I

cannot remember your name’.

She said, ‘I am that first great sorrow whom

you met when you were young.’

Her eyes looked like a morning whose dew is

still in the air.

I stood silent for some time till I said,’Have you

lost all the great burden of your tears?’

She smiled and said nothing. I felt that her tears

had had time to learn the language of smiles.

‘Once you said,’ she whispered, ‘that you

would cherish your grief forever.’

I blushed and said, ‘Yes, but years leave passed

and I forget.’

Then I took her hand in mine and said, ‘But you

have changed.’

‘What was sorrow once has now become peace’.

She said."

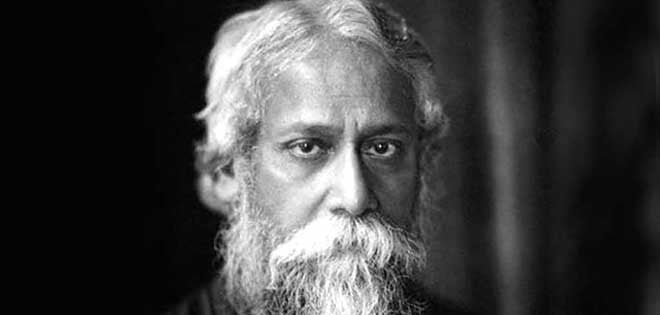

So wrote Rabindranath Tagore, the only Indian poet to have won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1913. Sorrow, he wrote, becomes peace. Sorrow turning into a calm solitude -- sorrow that passes and leaves along an enduring quality of suffering.

All his life Tagore believed in ‘suffering’. Suffering which gives depth and wisdom to life. Suffering that is not, for itself, but which transcends the misery of life and, over other emotions, compels us to enter a world where love of life and ‘milk of human kindness’ flows.

"It was growing dark when I asked her,’ ‘What

strange land have I come to?’

She only lowered her eyes, and the water gurgled in the throat of her jar, as she walked away.

The trees hang vaguely over the bank, and the land appears as though it already belonged to the past.

The water is dumb, the bamboos are darkly still, a wristlet tinkles against the water-jar down the lane.

Row no more but fasten the boat to a tree.

Let me seek rest in this strange land, dimly lying under the stars, where darkness tingles with the tinkle of a wristlet knocking against a water-jar."

There is, here, a sense of complete meditation, perfect communion between soul and eternity. In Tagore, poetry blends with all that is supreme, and man and God take their essence from love. Suffering is an essential part of love.

Tagore grew up in an era when Indian independence was just beginning to gain ground. Having made himself felt, having such a wide audience, it would have been easy for him to become a political leader. But he didn’t; instead he heralded cultural rapprochement between communities, societies and nations.

In his work the world of the unknown merges into a world ‘known’. He was not a nationalist in the sense in which we know the word. Freedom, absolute, freedom, and unfettered right to control their destinies is what he demanded for his countrymen.

"Where the mind is without fear and the

head is held high;

Where knowledge is free:

Where the world has not been broken up

into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of

truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms

towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not

lost its way into the dreary desert sand of

dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into

ever-widening thought and action

Into that heaven of freedom, my father, let

my country awake."

In 1900, Tagore opened his academy of Arts, Shantiniketan (House of Peace) in a secluded place in Bengal. At that time he must have thought that he would devote all his life to his academy. He did not want it merely to be an institution of learning. His ideal was to plan a home for the distracted spirit of India, where arts could flourish and prosper once again.

He wrote novels which deal with the social problems of the day. He wrote a score of dramas and dance-dramas in which he often acted himself. He wrote songs which he set to music himself. He wrote short stories about the down-trodden, he wrote fiery articles about political and economic issues -- and he painted.

But he is known chiefly for his poetry. W.B Yeats said, "Tagore’s lyrics display in their thought a world I have dreamed of all my life." It is the poet in Rabindranath Tagore who sees every situation. It is the poet who surrenders and bows to the mysteries of this world. For the first time, in his poetry, we heard our voice as in a dream. In his poetry there are all the aspirations of mankind. Only a small portion of his poetry has been put into English and we have to thank Tagore for this, for he himself made translations into English and thus captured some of the music and rhythm of the original Bengali.

By the turn of the 20th century the centre of Tagore’s poetry was phenomena and not the woman, the SHE. As yet his creativeness was inspired mainly by the ‘south wind’, the flood of morning light, the gold on the clouds and the eternal tragedies of life. This was the time when Tagore was attempting to bridge secular and religious poetry; now giving lyrical expression to his patriotism, now sounding a distinctly religious note to his lyrics. This was his most inspired period when he wrote poems exquisitely light in touch, tender with humour which is close to tears.

"The father came back from the funeral rites.

The boy of seven stood at the window, with eyes wide open and a golden amulet hanging from his neck, full of thoughts too difficult for his age.

His father took him in his arms and the boy

Asked him’ Where is mother?’

‘In heaven,’ answered his father, pointing to

the sky.

At night the father groaned in slumber, weary

with grief.

A lamp dimly burned near the bedroom door,

and a lizard chased moths on the wall.

The boy woke up from sleep, felt with his hands the emptiness in the bed, and stole out

into the open terrace.

The boy raised his eyes to the sky and long gazed in silence. His bewildered mind sent abroad into the night the question, ‘Where is heaven?’

No answer came; and the stars seemed

Like the burning tears of the ignorant darkness."

And to make this column a real tear-jerker let me quote the last few lines of the last poem he dictated before his death.

"Today my sack is empty. I have given completely whatever I had to give. In return if I receive anything -- some love, some forgiveness -- then I will take it with me when I step on the boat that crosses to the festival of the wordless end."