Of all the exhibitions, the NCA Annual Degree Show is the only one that invites us to take a shot at it -- impelling us to reject it, to quarrel with it, to debate the purpose of an exhibition as an aesthetic and intellectual experience.

Bigger and louder than its last incarnation, in 2013, the Annual Degree Show 2014 is also perhaps more commercial. Indeed, it holds its own in the context of the show’s distinguished history, and each previous installment has proved a fair barometer of its times. The Annual Degree Show at the NCA, Lahore, provided an early blueprint for art shows set in art departments in colleges and universities, and that blueprint has been adopted widely in the past decade, with small to midscale academies the country over grasping how useful visual art can be in forging a civic brand and, with it, a strong economy.

The NCA helped give birth to the proliferating art academies, and, like any parent, it faces the prospect of being exhausted by its clamorous brood. But what it lacks in youthful vigour it makes up for in experience, and this year it was evident.

Visiting the Annual Degree Show 2014 at the NCA, Lahore, one week after it opened, I was presented with the rather daunting challenge of trying to keep an open mind. Waves of negative opinion, sniping, and relentless gossip had all but hardwired themselves into my brain, and to set aside every enraged report and bitter lament of a colleague or friend who had already seen the show required an enormous effort. "Art does not sell in Lahore anymore", lamented one "but going by the red dots, almost everything sold before the opening of the Degree Show, this year, depriving those who waited until the official opening."

There is neither a policy nor an agenda when it comes to barter. Outsiders -- mainly potential buyers on a hunt -- were spotted loitering within the precincts of the college well after sunset, visiting artists in their studios on the quiet and striking pre-emptive deals. No wonder, the new slogan of the Degree Show sounded, ‘Everything is permissible in love and war and commerce,’ with fresh graduates’ work commanding abominable prices and Dubai-based clients unwilling to wait.

"It should be renamed as Lahore Art Fair as each student/artist has a booth to himself where private negotiations on the total number of zeros to follow the principal digit are conducted surreptitiously", complained another heart-broken collector whose five personal favourite canvases were already picked by a faculty member. Until not very long ago, works of art used to be thought of as splendid, desirable objects -- self-contained and static. That notion of art as a ‘commodity’ prevails to this day. "We had to raise the bar because the expense incurred on display was humongous, this year. On top of it, some of us had to clear our bills," quipped one of the fresh graduates.

If the Annual Degree Show is still a treasure trove of trens for early adapters, look for some cutting-edge art this year to feature a bevy of strong candidates. The confrontation with the profusion of reflections in Umar Nawaz’s sculptures is a shock that, I suppose, is meant to prompt visitors to adjust their aesthetic expectations. One is being introduced to the first of many mis-en-scenes; the stage is set for a series of theatrical gestures. In this literal hall of stainless steel mirrors, viewers perceive themselves -- surrounded by their own images, which recede in diminishing iterations toward a distant vanishing point -- as actors in a theatre of displacements.

Next to this enthralling glow, strings draw the viewer’s attention deeper into the maze: Sidra Ashraf’s Untitled, a voluminous installation built of polyester cords that turns large parts of the gallery into a drawing in three dimensions. The work may well explore a unique combination of performance, kinetic art, and sculpture as an extension of painting, and the gendered zones of experience associated with the umbilical cord, but it can surely be appreciated solely on formal grounds as an uncommonly graceful play of curved lines in space.

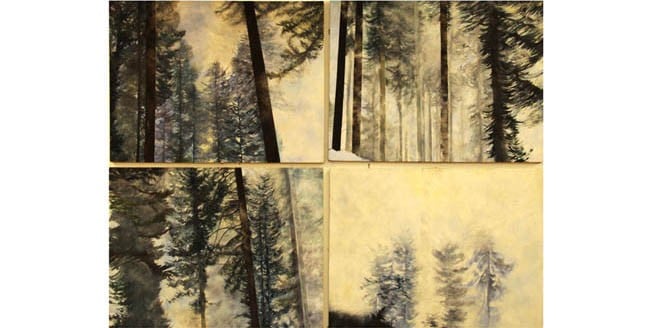

One still thinks of Anil Waghela as primarily a painter, although his paintings are not just paintings as he has been exploring their potential for plasticity. His aesthetic language relies on the flatness of the pigmented field and on the linearity of partially suggested shapes. And yet, the thinly laid colour are mere intense indications of hue as they enter grains of the surface to make it visible and to detach themselves as if gliding and abbreviating above it. Their translucency imbibes light and shadow and spreads along layers of space. The incomplete, briefly brushed but coarse-tender figures turn more dynamic and whimsical in their open-ended mode.

The wish for a work of art to come alive, which is the stuff of ancient myths, has materialised for Rahim Baloch. Even his earlier miniature paintings seem to strive for this to happen, as the emotionally loaded twists, meanders, splinters and mergers of shape and colour in his lyrically expressionist waslis almost free themselves from the ground. The realistic images that follow those use direct depiction yet do it to make tangible the presence of feelings, imagination and phantasmagoria among things factual, thus transforming the same. The near photographic and evocative then mutually enhance. Of late, the artist has brought such interaction to its climax by physically-aesthetically-emotively wedding brushwork to large waslis in an installation environ.

David Hume, in the first book of his Treatise of Human Nature (1739), argues that "the repetition of like objects in like relations of succession and contiguity, discovers nothing new in any one of them". Even though one might claim that a sophisticated theory and practice of resemblance would, as Barbara Stafford wrote in Visual Analogy, capture "those moments of connectedness when we most vividly sense that someone is at home inside our heads", it can be doubted that this is what the ontological pathos of this year’s Degree Show is really all about. Domesticity and domestic environment, relations and issues rule the roster, as always, and come as no grand surprise, even this time. A good measure of it is thrown in to balance the equation between the banal and the mundane, perhaps for the lack of anything serious and mature.

The Annual Degree Show, NCA’s success is such that it inflects the very air in which the contemporary art functions, lives and breathes; and it produces atmospheric effects that absolutely must be taken into account when seeking to articulate any critical appraisal of the year’s large-scale exhibitions. Regarding the Degree Show, one is bound to read in a breathy, gossipy tabloid that more art had been sold than ever, more money (tax-free) had been generated, more records broken, more competition accelerated; artists are designing exhibition booths, instant collections are established, and almost everyone’s appetites sated.