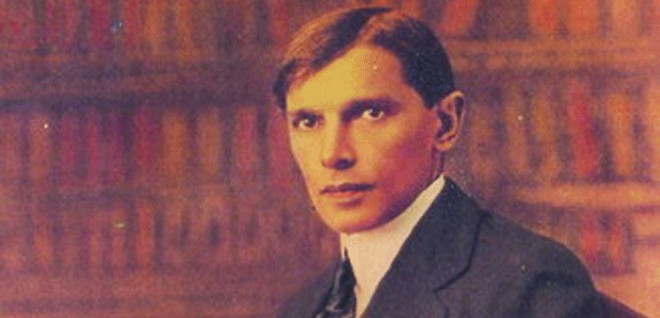

On the eve of Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s 137th birth anniversary, it seems pertinent to take a synoptic view of the discursive studies carried out on his life and achievements. Included in the huge corpus of literature produced on that subject are hagiographies, compilations of important documents concerning his political life, statements and speeches, biographies and scholarly studies, to list the broad principal categories.

Zawar Hussain Zaidi, Sharif ud Din Pirzada and Waheed Akhtar followed by Rafique Afzal and Jamil Ahmed have done compilations of important documents, which are handy resources for posterity for the use of researchers. Ayesha Jalal, Sharif ul Mjahid and Sikander Hayat have all produced scholarly works on Jinnah. Riaz Ahmed and Akber S. Ahmed too have contributed in this regard, but their works are the illustration of what Saeed ur Rehman calls "safe scholarship" whereby the authors take extremely cautious/conservative view of the subject that they deal with.

In the category of biography, Hector Bolitho, Stanley Wolpert, Liaqat Merchant, Jaswant Singh and Ajit Javed are credited to have produced biographies which are worth reading to say the least. Hagiographical literature on the founder of Pakistan is in abundance from Z.A. Sulehri to Chaudhry Sardar Muhammad -- works which at times appear to be trivialising the towering persona of Jinnah. Hagiographical literature on the founder of Pakistan is the seminal point made in the lines to follow.

Jinnah, along with Allama Iqbal, is being constantly imagined and re-imagined by an ever-increasing band of hagiographers and apologists. Undoubtedly, in Pakistan, the deification of these two personalities is divesting them of their human characteristics through churning out hagiographical accounts, a process which has proved to be the safest career option for many writers. One wonders if such placid studies, completely devoid of any novel intervention on the subject, are doing any good to the state of history or its allied disciplines in any way.

It can, however, be argued that the ‘transcendental signification’ accorded to these two great persons has arrested the growth of our political insight and critical thinking in general. Moreover, it has given sustained currency to the anachronistic notion of personalities being central to the culmination of any historical process. Such studies are akin to the traditional tazkira nigari, in which the person concerned was eulogized ad infinitum in a bid to make him look like a transcendental being, rather than proper biographies which deal with time-space bound mortals.

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan wrote Yadgar-i-Ghalib which is undoubtedly a classic. However, in the modern Muslim history of the Subcontinent, Altaf Hussain Hali (Hayat-i-Javaid, the life history of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan) and more importantly Shibli Naumani can be regarded as the pioneers of the genre of biography-writing (which were more like hagiographies). One must be mindful of the fact that Hali’s Hayat-i-Javaid is a finely balanced account and fulfills the criterion of a biography. Shibli, of course, was a trend-setter by putting together such works like Sirat un Nabi, Al Farooq, Al Ghazali, Al Mamun etc.

Shibli was inspired immensely by British historian Thomas Carlyle (1795-1881) whose book entitled Heroes and Hero Worship casts an indelible impression on Muslim laureates of 19th century India as S.M. Ikram alludes to, in his book Yadgar-i-Shibli. However, the biographies churned out ever since have a tangible rub of the style peculiar to tazkira writing. As a consequence the life-histories produced thereafter are devoid of any critical engagement with the subject of the study.

Thus any scholarly work with critical inflection is usually excoriated relentlessly by these Jinnah specialists. Many of them have the privilege of reaching out to a wider audience through the Urdu media, to which they contribute on a regular basis. Unfortunately, the general perception about the Pakistan’s history and politics is being formed by their writings, a fact that is highly regrettable.

It was because of them that after its publication, Ayesha Jalal’s The Sole Spokesman was virtually condemned by this species of hagiographers as if she had committed some heinous heresy. Late Prof. Sher Muhammad Garewal was visibly incensed when I suggested including that book in the Master’s course at GC University, Lahore. Ayesha Jalal, according to him, was unpatriotic and anti-Quaid-i-Azam and hence she should be condemned instead of including her works in the curriculum.

Now it is quite commonplace to quote the very first paragraph from Stanley Wolpert’s Jinnah of Pakistan which accords a glowing tribute to Jinnah that reads, "Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation state. Muhammad Ali Jinnah did all." But despite that it also was banned in Pakistan in the 1980s when Gen. Zia was at the helm. The reason for banning its circulation in the Pakistani market was the author’s audacity to unveil some of the ‘human’ (one can read ungodly too) aspects of Jinnah’s personality.

After Hector Bolitho’s book, Jinnah: Creator of Pakistan Wolpert’s Jinnah of Pakistan is one of the very few books which fulfils the criterion of a biography. Jaswant Singh, A.G.Noorani and Ajit Javed are other extremely important and acclaimed biographers of Jinnah. Their biographies are extremely significant because it is through such studies that one gets to know how Jinnah is being viewed from across the border.

It is because of the hagiographical nature of most studies on Jinnah in Pakistan that neither of those could create any ripples in the international academia. However, Liaquat Merchant and Sharif ul Mujahid are two exceptions in this regard. Merchant has employed some useful family sources in his study and Mujahid’s work, Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Studies in Interpretation is worthwhile because of the academic rigour and meticulous marshalling of primary sources, which are generally a hallmark of his scholarship.

As a concluding remark, it is argued that any historical account with critical insight does not amount to demeaning anybody. Great historical figures remain great even if someone comes up with a dissenting view about them. Rigid thinking engenders rigid behaviour which is nothing but a recipe for stagnation and decline.