Forty two years ago, on December 16, 1971 when the flickering flame of national unity died out, resulting in the cessation of East Pakistan, I witnessed two starkly contrasting reactions in my house. First, my youngest uncle, an impulsive second year student at King Edward Medical College, spanked Gen Yahya Khan’s photograph, expressing his pathos and poignancy by actually crying. Many people reacted in the same ‘impulsive’ way, which was quite typical of the Pakistanis. Such a reaction is, more often than not, quirky and momentary.

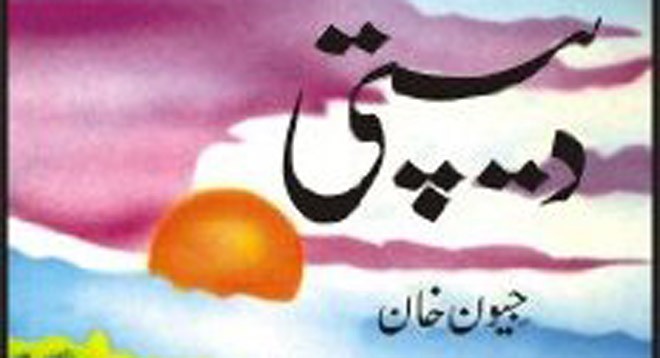

The second reaction was that of my father (Mr Jiwan Khan) which was a ‘contemplative’ response to the dismemberment of the country. He sat down to write a novel in Urdu, Deepti, set against the backdrop of East Pakistan. As a young civil servant, he had had the opportunity to serve in districts like Rajshahi and Rangpur in East Pakistan, where he had gained a decent smattering of Bengali language, an understanding of the pervading cultural ethos and sufficient knowledge of the riverine terrain of East Pakistan. This equipped him with the wherewithal to write a profound and pithy piece of literature.

That there exists such a limited corpus of literature on a subject of such vital importance attests to our collective inanity.

Through literature, cultural plurality can be celebrated and a sense of mutuality, in spite of our great diversity, can also be cultivated. Literary writing, or indeed writing on any realm of knowledge, is an extremely serious business. In the very act of ‘writing’ on any event, and particularly one that is tragic in its essence, the writer is meant to engage with it from a distance in order to view it dispassionately. Coupled with this distance, though it may seem to be a bit contradictory, the writer needs to have empathy and pathos, both essential stimuli for addressing such a theme through any literary genre.

The novel’s plot is about a Hindu Bengali girl, Deepti, who offers refuge to a West Pakistani officer, Ali Azam, posted in East Pakistan and running for his life in the midst of 1971 crisis. Coincidentally, he goes to her house and she hides him in a room that she and her family members occasionally use for a Puja of the goddess Kali. The fate forced a young Muslim man to spend a few days at the feet of a goddess, a despicable entity for any Muslim of the Subcontinent.

Deepti’s compassion for Ali Azam subsequently turns into a finer feeling of love. Eventually after many twists and turns in the story, Ali Azam manages to escape but ill-fated Deepti falls prey to the atrocities at the hands of those striving for Bengali liberation. She is raped and tortured and also separated from the son that she had with Ali Azam. Despite her physical torment, her soul remains devoted to the love of her life, Ali Azam, and thus the essence of her ‘being’ remains pure and unadulterated.

All of the confusion, carnage and killing had been a manifestation of the results of giving precedence to the ‘physical’ over the ‘spiritual’ which causes this travesty and which became Deepti’s destiny. In the novel, however, the primacy of the ‘spiritual’ does not shroud the ‘physical’ realities shaping up themselves with their corollaries and ramifications. Parallel to the main story is a graphic description of the agitation orchestrated by Bengali nationalists in various districts.

Bengali nationalists and their cause, of course, had the last laugh but at the cost of humanity (Insaniyat) because so many innocent souls, like Deepti, fell prey to the politics of hatred and exclusion. The novel is indeed a profound reflection on the way history unfolded itself in East Pakistan.

That novel did not attract the attention of many. One reason might be that the author had no clout in Pakistani literary circles, which is a prerequisite for the success of any author or his writing. But, more importantly, among the Pakistani public, engagement with tragedy and rupture has been markedly tenuous. I earnestly believe that tragedy and social and political upheavals provide a great stimulus for the best literature. An appreciation of the cause that conjures it up is also necessary.

It is important, though, that the processes underlying the tragedy, and the events which cause it to take place, are initiated for internal reasons. Quite contrary to that premise, Pakistanis, more often than not, attribute the cause of any tragedy to some extraneous factor like the Hindus, or the Jews, or the West, and therefore it does not become internalised. Instead, conspiracy theories start circulating and gain credence as an authoritative source.

We must learn to accept our deficiencies and shortcomings, and analyse properly the tragic situations that come to pass. Sensitivity to tragedy and a full cognizance of what it brings in its wake is absolutely essential for the cultural and political maturity of the people. Accepting the responsibility for our adversities will enable us to come up with a contemplative response to catastrophic situations instead of momentary and impulsive reaction. The strongest cultural responses to adversity come through literature, which is then able to inflect the national discourse.

Another point worth pondering is the absence of the present in our literary articulations. Nostalgia (with the past) constitutes an immensely strong component of our literary prose, as well as our poetry. Some conscious effort to bring the ‘present’ into the fold of literature would be an extremely worthwhile undertaking, one that could undoubtedly bring literature and politics together, as great literature cannot be produced independently of politics.

‘Smaller’ provinces hardly find any space in the mainstream cultural discourse in Pakistan. Cultural critique of the ‘political’ is absolutely vital for any polity, something that seems conspicuously missing in our milieu.