Multan may have been called Kashyapapura which became Hanspur, then Baghpura and eventually Mulasthana -- or as some trace the history to the conquest of Malis Than in 325-326 BCE by Alexander.

The original city comprised two mounds, the Fort now known as Qasim Bagh and the Walled City, separated by a moat fed by the river water. Later, the two mounds were referred to as Sikha and Multan, separated by the channels of River Ravi.

Soon after Ravi changed its course and joined the Chenab, which flows adjacent to the city of Multan now.

Thousands of devotees congregated at the two revered sites in the Fort -- the Sun Temple and the Prahladapuri Temple. Retaining its spiritual character, subsequently, during the Muslim period, it became a centre of Islamic learning.

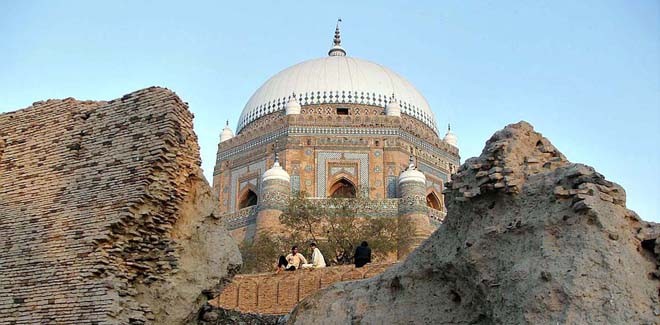

Multan: A Spiritual Legacy is primarily a study of some of the most important monuments of the city, its architectural peculiarities, descriptions and technical drawings. It can easily qualify to be a splendid effort at understanding the rich architecture of the ancient Multan, which some believe vies with Damascus as the oldest living city in the world.

The focus has been the Fort and then the Walled City monuments to east, west and south of it, along with the Ali Akbar complex, the shrine of Musa Pak Shaheed and the mosque by the same name in Uch Sharif.

A few years ago, the Ministry of Culture awarded a project for the ‘Preliminary Survey and Studies for the Preparation of Conservation Plan Preservation and Restoration of the Historical Monuments of Multan’. A list of historical monuments was provided for complete documentation, topographical survey of the site, historical background, intervention study and an environment assessment. The result is a beautifully produced coffee-table book with plenty of vital architectural details as well as general information.

Some of this information, especially the archival photographs and maps were gleaned from the rich treasure troves of the British Library in London and Punjab Archives in Lahore. The edition is lavishly illustrated with breathtaking photographs by none other than Sami-ur-Rehman.

The buildings listed are the Fort, Faseel, Khuni Burj, Bohar Gate, Jain Mandir, Gopal Mandir, Haram Gate, Delhi Gate, Ghanta Ghar, Suraj Kund Temple, Tank Shrine of Hazrat Sher Shah, shrines of Bahauddin Zikria, Rukne Alam, Yousaf Gardazi, Musa Pak Shaheed, Sakhi Yahya Nawab, Pir Inayat Willayat, Hamid Gilani, Shah Ali Akbar, Shah Shams Subswari, Allah Dad Gurmani, Pir Khawaja Ali Mardan Awaisi, Khawaja Awais Khagga, tombs of Shahdana Shaheed, Saeed Khan Qureshi, Pir Mian Daler, Ali Akbar mother, Mai Meherban, Shah Hussain Saddozai, Bibi Pak Damina, mosques Musa Pak Shaheed, Ali Wali, Tarkhana Wali, Ali Akbar, Hafiz Jamal, Eid Gah, Swi Masjid, Wazir Khan, Khuddaka Dharamshala Dyal Singh, Barood Khana, Damdama, Prahladapuri Temple and memorials of Patrick Alexander and William Anderson.

Before the conquest of Alexander it was a province of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. But the documented history started with the Greeks Herodotus and Arrian. The first evidence of Muslim influence came during the period of Umayyad Caliphate in 664 when an Arab General Al Muhallab bin Abi Suffrah, went back with booty and slaves. But in 712, Muhammad Bin Qasim integrated it into the Muslim regions.

For the next 300 years, the Arabs continued to attack the place because it had become a vassal state of the Fatimids till Mahmud Ghaznavi finally conquered it in 1005 ending the Qarmatians rule and destroying the Hindu temples.

The internecine and sectarian bloodletting too has been as much the cause of conflict in the Muslim world, forming a crucial part of our history as the much-touted battles and wars that were fought with the infidels. The sharp edges of religious and sectarian differences were blunted by those who preached tolerance and peaceful coexistence and, this city, a little later, became the centre of learning and pilgrimage -- thronged by the Sufis for 300 years.

Uch Sharif too has a similar history, as evident from the large number of Sufi monuments and shrines there.

But since the shrines and other buildings are spread over the entire millennium, it became an architectural recount of the history of the city with its many vicissitudes. The period of Shah Muhammad Yousaf Gardezi, the first saint and the monument to be documented in the book was around 1086, the last were of the British colonial-era.

Thus this study covers almost the last thousand years.

The write-ups on the buildings also reveal the various changes that have been made to the old structures, the efforts at repairs, extensions, demolitions, restorations over a period of time. Through this document one can get a good understanding of the life of the city of Multan over 3000 years. It also refers to some monuments in Uch Sharif, which too was a centre of learning and housed many a scholars, some of whom are buried there. As the two centres interacted it is possible that the two were sister cities.

It is a treasure trove for those interested in the Sultanate period architecture. But not all buildings are well-maintained. There is an urgent need to restore not only the buildings and monuments but the city as it was planned and may have looked like during some period of its glory. The rapid expansion of the cities, poverty, population explosion, non-observance of building and municipal rules, managed encroachments and above all limited resources have destroyed most of our old cities.

Such work can at least pave the way for the planners and restorers to start thinking about giving back to the old cities their actual look. Probably, in this case, some headway has been made by putting on ground a few of the suggestions proposed in this document.

But this can only be achieved fully if backed by political will and real intent.