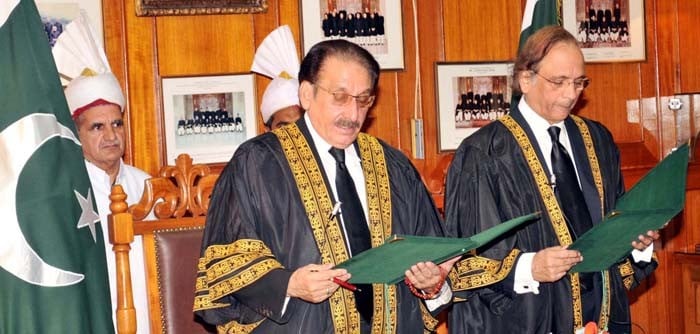

With the appointment of Justice Tassaduq Hussain Jillani as the next Chief Justice of Pakistan from December 12, 2013, on the retirement of Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, there is enthusiasm in official circles that the "era of undue intervention in civil-military administrative affairs and political arena" will come to an end. They hope that Justice Jillani, known as "the gentleman judge" for his mild manner, would maintain focus on rights but "steer clear of intervening in government policy". They say Justice Tassaduq Hussain Jillani avoided the high-profile political cases that Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry revelled in.

According to them, Justice Tassaduq Hussain Jillani as Chief Justice of Pakistan would prefer "judicial vigilance" over "judicial populism". "If the courts fail to maintain this delicate balance, none else but people’s confidence in the judiciary would be the worst victim", Justice Tassaduq Hussain Jillani observed in a recent ruling.

While the controversies and debates over the role and legacy of outgoing Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry would continue, it is the time that new chief justice starts some fundamental reforms in the existing judicial system -- and Justice’, The News, October 27, 2013.

Our judicial structure, dating back to the British colonial era, has not changed except patchwork of so-called Islamic laws and establishment of Federal Shariat Court by General Ziaul Haq. Two conflicting legal systems have given undue advantage to the police alone for self-aggrandizement rather than serving any useful purpose for dispensation of justice in the real sense of the word. The maxim ‘justice delayed is justice denied’ most aptly describes the essence of our judicial system which desperately needs reforms at all levels.

On August 14, 1947, we inherited a strong and independent judiciary having unquestionable reputation of competence and integrity. Mian Abdul Rashid, the first chief justice of Pakistan, was a man of unimpeachable character, who restrained from attending government gatherings and public functions. His successor, Justice Muhammad Munir, for his judgements in Maulvi Tamizuddin case [PLD 1955 Federal Court 240] and few others did become controversial, though his critics seldom realise that it was actually the failure of the political elite that paved the way for recurrent unconstitutional rules for which judiciary could not alone be blamed. One cannot, however, forget some of his great successors like Justice Shahabuddin and Justice A.R. Cornelius, who demonstrated high standards of judicial conduct even in the earlier tumultuous years of our political history.

In the post-independence years, the dilemma of our judiciary remained perpetual failure of political leadership as it was approached many a times to determine the validity or otherwise of capturing state power by men in uniform. In The State v Dosso [PLD 1958 SC 533], Chief Justice Muhammad Munir called it a "successful revolution", but Justice Hamoodur Rehman in Asma Jillani v Government of Punjab [PLD 1972 Sc 139] called it "usurpation" of people’s rights. In Begum Nusrat Bhutto v Chief of Army Staff [PLD 1977 SC 657] came yet another endorsement of the doctrine of necessity wherein "intervention" was declared lawful "in the best and larger interest of the nation. General Musharraf not only got three years but also the right to amend the Constitution! However, defiance and an emphatic ‘NO’ by Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry to same Musharraf changed the entire judicial landscape.

For judiciary, November 3, 2007 was the beginning of a new era. A dictator imposed judiciary-specific martial law -- this time the victims were not politicians but the judges. For the first time, it was issue of survival for those who always sided with men in uniform against politicians. The effectiveness of people’s street power that reigned from March 9, 2007 to July 20, 2007, from November 3, 2007 to March 16, 2009 -- culminated in the second restitution of Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry as the Chief Justice of Pakistan on March 22, 2009.

As March 16, 2009 brought "justice" for Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, the Supreme Court as an institution conveyed a change of mind in its decision of July 31, 2009 as under:

"Before parting with the judgment, we would like to reiterate that to defend, protect and uphold the Constitution is the sacred function of the Supreme Court. The Constitution in its preamble, inter alia, mandates that there shall be democratic governance in the country, wherein the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance and social justice as enunciated by Islam shall be fully observed; wherein the independence of judiciary shall be fully secured. While rendering this judgment, these abiding values have weighed with us. We are sanguine that the current democratic dispensation comprising of the President, Prime Minister and the Parliament shall equally uphold these values and the mandate of their oaths".

The above judgement highlighted the real dilemma faced by Pakistan since its existence -- a daunting challenge of establishing true democratic polity based on constitutional supremacy, rule of law and equity. The long military rules -- backed by foreign masters -- and in between experiments of "controlled democracy" denied the people of Pakistan their sovereign right to self-governance, for which a long struggle was waged to secure independence from the British raj. The dictatorial rules stifled all the state organs -- especially judiciary that became an approving arm for many unconstitutional rules.

Supreme Court, after restitution of Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, started taking up many cases, some using suo muto powers, causing panic in many circles. Political polarisation diluted valiant common struggle waged by all segments of society, most notably by lawyers, media, social and political activists, for restoration of an independent judiciary. The PPP government alleged that apex court was transgressing its constitutionally-defined limits. Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry said that if people were not getting their rights, the judiciary was bound to be proactive.

It is an undeniable fact that in the post-March 16, 2009 scenario, the judiciary under Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry failed to deliver to the people as no reform agenda was implemented to remove snags in the dispensation of justice. The justice system remained hopelessly redundant, painfully unproductive and marred with inefficiency and inordinate delays. Since March 2009, apex court is in conflict with all other state institutions.

There will be a great challenge before Justice Tassaduq Hussain Jillani as the next Chief Justice of Pakistan--his will retire on July 6, 2014--to restore the "balance" he has openly spoken about. The real goal should be to make the judicial system capable of delivering justice without delays and heavy costs to litigants.

No doubt the apex court and higher courts are constitutionally obliged to curtail arbitrary exercise of powers by any organ of the state as their main role is protection of fundamental rights of citizens under all circumstances. It should remain their first and foremost duty. While maintaining the supremacy of Constitution, a sanctimonious document representing and expressing the supreme will of the people, the court should also ensure quick disposal of conflicts pending with them.

Tragically, our courts are still following the outdated procedures and methods whereas many countries have adopted e-system for filing of cases and their quick disposal through fast-track follow up using the offices of magistrates at grassroots levels. The main aim of judicial reforms should be elimination of unnecessary litigation and facilitating smooth running of affairs between the state and its citizens. Once both learn to act within the four corners of law, there would be no need for enormous litigation. It is shameful that presently the government is the main litigant. It usurps the rights of people and then drags the poor citizens in courts.

First of all, the apex court under new chief justice should establish a commission to determine the reasons for this morbid state of affairs. The principles underlying reforms should not mean forcing unnecessary litigation and then its quick disposal but to help reduce its occurrence in the first instance.